Though normally dedicated to the consumption of luxury goods, last Sunday’s edition of the New York Times Magazine supplement featured an article by Barbara Ehrenreich about union organizing efforts among nannies and other domestic workers in New York City. Ehrenreich, whose own experience as a low-wage worker for a housecleaning service, is chronicled in the classic and highly recommended Nickel & Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, profiles labor organizer Ai-Jen Poo, who in turn describes the plight of one worker from Jamaica:

Alice had been lured to this country at age 16 with the promise that she would be able to go to school while working as a live-in nanny and housekeeper. Once she arrived, however, she found that school was not on the agenda—Alice’s domestic duties filled her time from early morning till late at night—nor, according to Poo, did she ever see a paycheck. The couple who employed her claimed they were sending her wages straight home to her parents, and since they controlled her access to mail, both incoming and outgoing, she had no way of finding out that no money was sent. After working without pay for 16 years, and cut off from her parents, who thought she had abandoned them, Alice escaped from her “employers” with help from one of their three young children. (“The Nannies’ Norma Rae: Ai-jen Poo Fights for Domestic Workers’ Rights, NYT Magazine supplement, 5/1/11, p. 50)

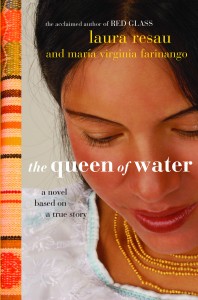

This story is depressingly familiar to readers of Laura Resau’s new novel based on a true story, The Queen of Water, and it highlights the fact that what happened to her co-author María Virginia Farinango in Ecuador in the 1980s is happening today. In the United States. And it will continue to happen if workers do not have the right to organize and if the government at all levels refuses to defend the poor and powerless against the well-heeled whose donations fill their campaign coffers.

This story is depressingly familiar to readers of Laura Resau’s new novel based on a true story, The Queen of Water, and it highlights the fact that what happened to her co-author María Virginia Farinango in Ecuador in the 1980s is happening today. In the United States. And it will continue to happen if workers do not have the right to organize and if the government at all levels refuses to defend the poor and powerless against the well-heeled whose donations fill their campaign coffers.

Like many indigenous children in Ecuador, seven-year-old Virginia Farinango was sent by her impoverished parents to work for a mestizo (light-skinned, mixed-race) family that abused her and broke their promise to pay her and to give her an education. However, the lively and ambitious girl overcame her feelings of inferiority and learned to read, then secretly borrowed the textbooks of her masters, both teachers, to teach herself science and history. Resisting the wife’s regular beatings and the husband’s sexual advances, Virginia eventually escaped their household, returned to her family, and worked her way through high school and to a better life.

Resau does a masterful job of giving her collaborator’s story shape and dramatic tension. Farinango doesn’t idealize her life before being sent to work as a servant, but readers see the strength and independence that she gains while growing up in a poor indigenous community. Her masters are portrayed as complex people with their own problems, and Virginia’s attachment to the two boys in her care make it all the more poignant when she must make the choice to stay or run away. The collaboration between Farinango and Resau has resulted in a powerful, well-paced story that will appeal to teen and adults readers alike, and is certain to generate lively discussion in classrooms and book clubs.

I interviewed Resau twice over the past two months, and later this week will post an interview with her on this site. In addition, my co-blogger Nancy Bo Flood will feature Resau’s middle grade novel Star in the Forest in June. The story of an undocumented Mexican immigrant family struggling to survive in a suburban trailer park after the 11-year-old protagonist’s father has been arrested and deported to Mexico, Star in the Forest was just named the state of Colorado’s Children’s Book of the Year.

4 comments for “Domestic Slavery: A Review of The Queen of Water”