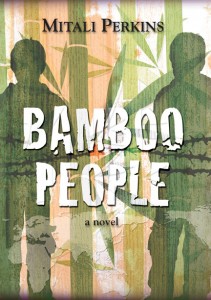

My review of Abe in Arms two weeks ago focused on the continuing struggles of a former child soldier in Liberia to overcome the trauma of a violent childhood. As Abraham Odo (his name before being adopted by the Elders family), Pegi Deitz Shea’s protagonist joined a rebel group at the age of 12 in order to protect his family living in an area occupied by the rebels. Chiko, Mitali Perkins’s 15-year-old protagonist in Bamboo People (Charlesbridge, 2010) has no choice but to fight. He has come to a closed-down school, lured by the possibility of a teaching job. In fact, he and the other young people brought there by a variety of ruses, are forcibly conscripted into the army of a repressive military dictatorship.

Bamboo People explores the situation of child soldiers in Burma (renamed Myanmar by the military government) and in refugee camps across the border in Thailand. Chiko, a studious city boy whose father, a doctor, is already in prison for criticizing the government, narrates the first half of the story. The second half is told from the point of view of 16-year-old Tu Reh, a refugee from the minority Karenni ethnic group. The Karenni are among several minority groups under attack from the military government, and Chiko has been taught to hate the Karenni as the “Kayah…determined to destroy our foundation of stability and the hope for progress.” In the army Chiko befriends a fellow draftee, Tai, and teaches Tai to read. The two become friends, and Chiko saves Tai’s life, though in doing so he puts himself in danger and in the path of Tu Reh. Though angry with the Burmese soldiers who burned his home, killed his people, and forced his family into exile in Thailand, Tu Reh finds common ground with Chiko. Their budding friendship forces Tu Reh to stand up to fellow refugees who see Chiko as the enemy and want to execute him.

Bamboo People explores the situation of child soldiers in Burma (renamed Myanmar by the military government) and in refugee camps across the border in Thailand. Chiko, a studious city boy whose father, a doctor, is already in prison for criticizing the government, narrates the first half of the story. The second half is told from the point of view of 16-year-old Tu Reh, a refugee from the minority Karenni ethnic group. The Karenni are among several minority groups under attack from the military government, and Chiko has been taught to hate the Karenni as the “Kayah…determined to destroy our foundation of stability and the hope for progress.” In the army Chiko befriends a fellow draftee, Tai, and teaches Tai to read. The two become friends, and Chiko saves Tai’s life, though in doing so he puts himself in danger and in the path of Tu Reh. Though angry with the Burmese soldiers who burned his home, killed his people, and forced his family into exile in Thailand, Tu Reh finds common ground with Chiko. Their budding friendship forces Tu Reh to stand up to fellow refugees who see Chiko as the enemy and want to execute him.

Along with a gripping story, Perkins provides a detailed section of background information and links for readers to get involved at www.bamboopeople.org. Burma/Myanmar is one of the principal exploiters of child soldiers, and the government has persecuted ethnic and religious minorities since it gained power in a coup in 1962. The most visible pro-democracy leader, 1991 Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung Sun Suu Kyi, was held under house arrest for most of two decades, winning her release only last November with heavy restrictions on her, and her supporters’, political participation. Thousands of less visible activists like Chiko’s father continue to endure torture and horrendous living conditions in the country’s vast network of political prisons.

While Chiko is forcibly conscripted, Tu Reh fights to protect his family and community. The land mine placed by the refugees to keep soldiers from invading the camp mangles Chiko’s leg, leaving him crippled at the age of 15. Still, Tu Reh advocates for saving the younger boy’s life; his concept of self-defense doesn’t extend to executing a helpless soldier who no more wants to be where he is than Tu Reh does. For many children and teens, the war going on around them leaves little choice but to kill or be killed, with scarce opportunities to show mercy or find common ground.