At the regional IBBY conference in Fresno last month, three of us from The Pirate Tree spoke on a panel about war and children’s literature. The books we discussed were for the most part realistic depictions of war past and present.

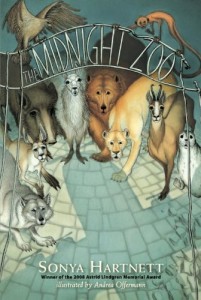

Some authors, however, have chosen to weave elements of fantasy into their stories of real events. The blending of fantasy and reality through magic realism and other styles can connect readers to the folklore and cultural traditions of the characters, as J.L. Powers does so well in This Thing Called the Future. It can also make the connection between specific events and universal truths and depict horrific events at one remove, making those events at once less frightening and more poignant. This is what Australian author Sonya Hartnett accomplishes in her 2010 novel The Midnight Zoo, published in the U.S. by Candlewick

Some authors, however, have chosen to weave elements of fantasy into their stories of real events. The blending of fantasy and reality through magic realism and other styles can connect readers to the folklore and cultural traditions of the characters, as J.L. Powers does so well in This Thing Called the Future. It can also make the connection between specific events and universal truths and depict horrific events at one remove, making those events at once less frightening and more poignant. This is what Australian author Sonya Hartnett accomplishes in her 2010 novel The Midnight Zoo, published in the U.S. by Candlewick

Two young boys and their infant sister, Romany children who are fleeing the Occupation soldiers who have attacked their caravan, pass through a bombed-out village and find a small zoo, still intact, on the village outskirts. At midnight, the desperate, starving animals begin to talk to 12-year-old Andrej and his nine-year-old brother Tomas. The children and the animals share the circumstances that brought them to the zoo, their longing for family members lost as a result of the war, their feelings about who is to blame for the war, and the meaning of freedom. For caged animals who can no longer survive in the wild and for two boys who must care for their sister, not knowing the fate of their mother, freedom and life are burdens, but still worth the struggle.

Although the cataloging information identifies this as a book about the Second World War and the Nazi persecution of the Romany people, the author deliberately keeps vague the references to real events. For instance, she does not identify the language on the signs in the zoo. In fact, the signs are in Czech, and I suspect that the events recounted were inspired by the 1942 assassination of the notorious Nazi commander and Hitler confidante Reinhard Heydrich. As a consequence of this assassination carried out by the Czech resistance, an enraged Hitler invoked the doctrine of collective responsibility to level several Czech towns, the largest one Lidice, and kill their inhabitants. There is a small but powerful museum exhibit in the Church of St. Cyril, which gave shelter to the resistance fighters, that my husband and I saw when we visited Prague several years ago. The offering of the lions to the Leader, described in The Midnight Zoo, was symbolic of efforts to appease Hitler, both at the time Czechoslovakia was divided up (the 1938 Munich Agreement and the later occupation of the country after splitting Slovakia from the rest) and the occupied citizens’ feelings, as Hartnett addresses the willingness of so many to collaborate with the invaders.

The vagueness of the historical setting seems entirely appropriate in a novel that uses magic realism so effectively. The talking animals, the itinerant human characters who are eternal outsiders, and the menacing landscape turn a specific war and a specific event in that war into a universal story of characters caught between their desires for freedom and survival.