Some readers might know that I’m in Portugal right now and will be here until the end of the year, as my husband has a visiting professorship. This afternoon I was looking at the bookshelf of the young woman from whom we’re renting our garret apartment, and I saw a large glossy exhibition catalog titled Aljube: A voz das vítimas (Aljube: Voice of the Victims). My reading ability in Portuguese is pretty decent, so I started in on the book, which consists of testimonials from former political prisoners, most of them incarcerated at the notorious Aljube prison, and descriptions of the judicial methods of the fascist regime that ruled the country between 1926 and 1974. (This is the same fascist regime that required only three years of education and banned certain fields of study, so that barely more than one-quarter of Portuguese adults have a high school diploma and the country ranks at the bottom of the European Union in terms of educational attainment.)

Today, Portugal has a democratic government, but the country still bears the scars of decades of dictatorship. Other countries are not so fortunate. One of them is China, where an unknown number of writers, labor and environmental activists, and others remain incarcerated despite the efforts of PEN, Amnesty International, and other organizations to free them or at least improve their living conditions.

Today, Portugal has a democratic government, but the country still bears the scars of decades of dictatorship. Other countries are not so fortunate. One of them is China, where an unknown number of writers, labor and environmental activists, and others remain incarcerated despite the efforts of PEN, Amnesty International, and other organizations to free them or at least improve their living conditions.

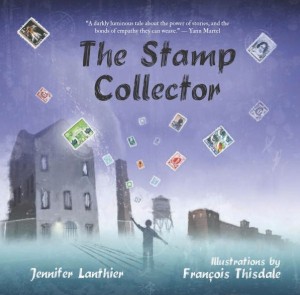

Published by the Canadian publisher Fitzhenry & Whiteside, The Stamp Collector is a powerful picture book inspired by two Chinese writers, Jiang Weiping and Nurmuhemmet Yasin, who spent years as political prisoners; Yasin is still there, serving a ten-year sentence. Jennifer Lanthier’s poetic text, with haunting illustrations by François Thisdale, describes of two boys in China—one from the city and one from the country. Both are poor. The city boy, who loves to collect stamps, grows up to take a job as a prison guard to support his family. The country boy sees his land polluted and endures difficult conditions at the factory where he finds work, and when he writes about his life, he ends up in prison. The city boy becomes his guard. He collects the stamps from all the letters written in support of the country boy, letters that come from all over the world.

Many of these letters are written by children, showing that it is never too early to introduce young readers to the concept of human rights. Basic principles of how we treat each other in our families, classrooms, and communities apply to groups of people and governments too. I would recommend this picture book to students in first grade and up. Young readers should be forewarned that one of the main characters dies in the course of the story, but this too is part of why we need to speak out for human rights.

5 comments for “Human Rights for Kids: A Review of The Stamp Collector”