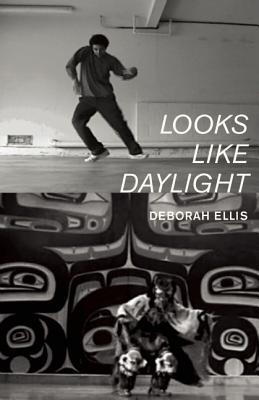

LOOKS LIKE DAYLIGHT by Deborah Ellis, Foreword by Loriene Roy

Sit down. Open this book, LOOKS LIKE DAYLIGHT. You will be surprised. Deborah Ellis traveled across the North American continent – the U.S. and Canada – to interview Native American and Aboriginal teens. LOOKS LIKE DAYLIGHT is her collection of their responses. They tell their own stories and they express their unique perspectives. Their voices speak with a simple and poignant honesty.

As you read these individual descriptions of families, friendships, and their hopes and disappointments, you will feel an intimacy as if you were sitting in a junior high or high school classroom and listening as thoughtful – and hopeful – young people speak from their hearts.

What does it mean to be a Native American or an Indigenous kid in today’s western world? In the U.S. over three million people identify themselves as Native. They are part of 565 federally recognized tribes. In Canada, there are 617 First Nation communities. Statistics tell us that to be Native means you are likely to live in poverty, die young, and drop out of school. But statistics do not tell about the individuals “who are learning from the struggle and courage of the people who went before them, about the countless hours spent in community organizing, and about the determination to create a better future that will honor the pain of the past.” (From Deborah Ellis’s Author’s Note)

Some individuals, like Tingo, age 14, have experienced many losses – family and home, friends and school. Tingo’s mother is Blackfoot and his father is a war refugee from Nicaragua. Tingo looks after his younger brother who is smart but his behavior is a problem because of brain damage from their mother’s drinking (FASD). Tingo says, “…he gets frustrated and he gets into trouble all the time. Teachers don’t really see him. They just see a problem….” Now Tingo and his brother finally are living in a stable situation, in reliable foster care. Tingo studies hard, is doing well in school, goes to guitar lessons on Mondays and then Sister Talk and Brother Talk on other days after school. He is the leader of Turtle Huddle where he helps little kids like his brother make drums and rattles and learn about traditional customs. At Sister Talk and Brother Talk teens learn about how to be part of a healthy family and talk “ a lot about grief because that’s been a big part of our lives as Native people – grief over losing our land, our language, our customs, our ways. Grief often comes out as trouble.”

In another interview, Mari, age 14 and Leach Lake Ojibwe, lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She goes to a classical private school and studies Latin, algebra, the Bible, theology and the Greek and Roman classics. As an Ojibwe young woman she learns and practices the traditions of her culture. “I do the Full Moon ceremony to celebrate a woman’s moon time and I do the Dark Moon ceremony, which is like a sweat but in a dark room….It makes me feel happy to do these things. Whether it’s me doing it today or another Ojibwe woman doing it five hundred years ago, it ties me in with her and with all the other Ojibwe. It makes me feel hopeful….”

With other Native teens, Mari has been working on an anti-smoking project, the Mashkiki Ogichidaag Project, which means Medicine Warriors.

Xavier, age 10, is a member of the Nez Perce tribe of Idaho, and he works hard to continue to be an outstanding student and someday become an engineer or university professor like his parents. He trains equally as hard to become a champion athlete, also like his parents. Already Xavier won first and second place medals at the USATF National Junior Olympic Track and Field Championships. One great aspect about sports, according to Xavier, is that “It doesn’t make a difference to people in Spokane that I’m Native. In sports it’s all about the sport, not about who’s white and who’s Native…But there is something special about being on the reservation and you’re surrounded by people who have your blood and the same history.”

Throughout this collection, Native teens describe their hopes and passions – their work to help seniors with transportation, their goals to become doctors to help others heal, and their work as leaders in their communities to protest against corporations who have sought to steal timber, water and other resources from Native lands. Many of these young people work with other teens to decrease the epidemic of suicides, alcoholism and school dropouts.

This is not a depressing book. Your eyes will be opened.

And so will your heart.