For the past several years I have been photographing scenes and creating stories using Lego minifigures, and my work in this medium has led to my wider reading of graphic novels. I have become acquainted with the great variety of visual styles, literary genres (no, these aren’t all fantasy/superhero stories), and themes. I am currently on the first round graphic novel panel for the Cybils, an award given by bloggers to outstanding children’s and young adult books.

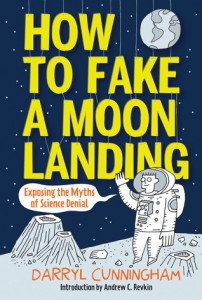

Darryl Cunningham’s How to Fake a Moon Landing: Exposing the Myths of Science Denial (Abrams, 2013) is not a graphic novel, strictly speaking, but a series of essays presented in graphic-novel form. Cunningham, a British science writer and cartoonist, takes on seven controversies over the past 50 years – conspiracy theories that the 1969 moon landing was faked; homeopathy; chiropractors; allegations that the MMR vaccine causes autism; the denial of evolution; belief in the safety of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking; and climate change denial. A concluding chapter surveys the deadly consequences of science denial.

Darryl Cunningham’s How to Fake a Moon Landing: Exposing the Myths of Science Denial (Abrams, 2013) is not a graphic novel, strictly speaking, but a series of essays presented in graphic-novel form. Cunningham, a British science writer and cartoonist, takes on seven controversies over the past 50 years – conspiracy theories that the 1969 moon landing was faked; homeopathy; chiropractors; allegations that the MMR vaccine causes autism; the denial of evolution; belief in the safety of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking; and climate change denial. A concluding chapter surveys the deadly consequences of science denial.

The artwork makes Cunningham’s arguments more tangible, as skeletons and skulls accompany his account, for instance, of people who sought unproven homeopathic treatments over mainstream medicine for cancer and other serious diseases. These visual aids are particularly effective in showing how technologies such as fracking work, and how they can potentially fail. Readers are also treated to a gallery of heroes and villains, including the doctor who, for personal gain, falsified studies to connect vaccines to autism. Each essay is supported by a list of sources from the popular media, government, and peer-reviewed publications.

Some of the essays, notably the ones on homeopathy, chiropractors, and the vaccine scandal, relate more to the author’s native Britain than to readers in the U.S., where, for instance, chiropractors do not have the same cult-like ideology (though the dangers of neck manipulation are the same). However, the book does broaden readers’ focus to hotly debated issues as they affect people not only in the U.S. but throughout the world as well.

The greatest strength of Cunningham’s graphic essays, though, is not in their treatment of the individual issue but in their exploration of how science works and why the scientific method is more useful than blind faith and conspiracy theories. The title essay shows why real conspiracies are so difficult to carry out, in this way debunking conspiracy claims that would have involved many collaborators. The essay on the MMR vaccine also discusses the ethics of using human subjects in research. The essay on evolution defines what a scientific theory is, and the ones on fracking and climate change call for the separation of scientific research from politics.

In his two-page introduction, scientist and New York Times science writer Andrew Revkin cogently places How to Fake a Moon Landing in a broader context, one that encourages the reader to do his or her own research and draw conclusions, including ones that challenge those of the author. Leaving aside any specific argument or essay, this is what the book is all about.