While it did not claim the top prize, it’s easy to see why Gene Luen Yang’s latest work, the two-volume set Boxers and Saints (First Second, 2013), was a finalist for this year’s National Book Award. Like in his National Book Award Finalist and Printz Award winning American Born Chinese (First Second, 2007), in Boxers and Saints Yang explores issues of identity and cultural conflict with humor and truth, using skilled illustrations and the layered storytelling of the graphic novel form to infuse the stories with added dimension.

While it did not claim the top prize, it’s easy to see why Gene Luen Yang’s latest work, the two-volume set Boxers and Saints (First Second, 2013), was a finalist for this year’s National Book Award. Like in his National Book Award Finalist and Printz Award winning American Born Chinese (First Second, 2007), in Boxers and Saints Yang explores issues of identity and cultural conflict with humor and truth, using skilled illustrations and the layered storytelling of the graphic novel form to infuse the stories with added dimension.

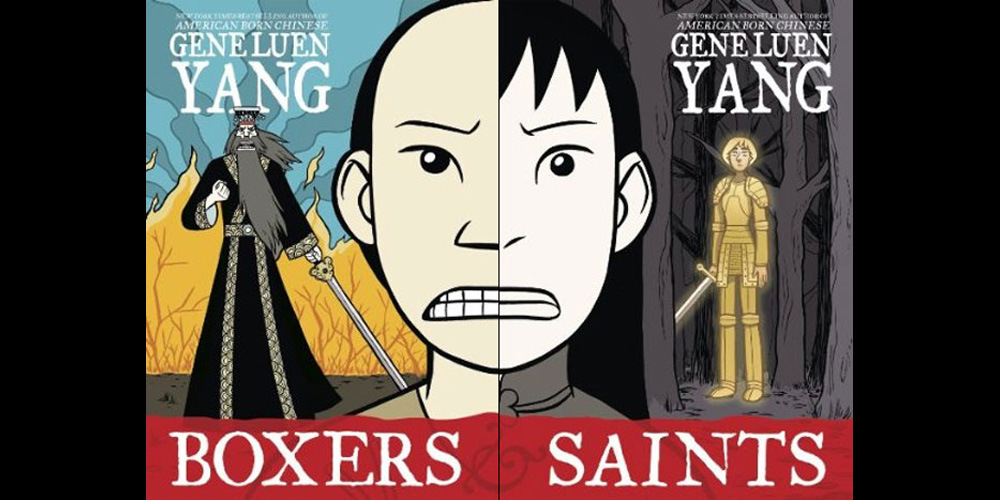

Boxers and Saints is a two-volume graphic novel (sold separately and packaged together as a set), which explores the Boxer Rebellion in China at the turn of the 20th century through two very different adolescent point of view characters.

In Boxers, Little Bao, a peasant third son joins the Boxers and rises to a position of leadership in the mystically inspired society of young Chinese men fighting to rid China of the “Foreign Devils” (Western soldiers and Christian missionaries) and punish the “Secondary Devils” (the Chinese converts to Christianity). While firmly set in the reality of the Boxer Rebellion, Little Bao communes with the mystical spirit of Ch’in Shih-huang, China’s first emperor, and becomes a mystical warrior god for his people, righteously killing to take back China from foreign influence and missionaries, until he has become as monstrous as those he considers his enemies.

In Saints, an unwanted and ostracized girl, barely given a name by her family, converts to Christianity and strives to find meaning and purpose — along with her new proper name Vabiana — within her new faith. However, her course is hampered by the fact that her conversion is less about religious fervor, and more about a misplaced hunger to belong. Mystically inspired and befriended by the spirit of Joan of Arc, Vabiana works to find her role — priest, wife or warrior for her people — but she is struggling to determine who she is after years of feeling unwanted, confused by her new faith, and stifled by the constraints placed on her as a girl.

Where these two stories intersect there are no easy answers or pretty endings. Perhaps most telling, neither is victorious or unscathed. Neither can be seen as entirely right, nor entirely wrong. Yang explores both the colonial exploitation by the Westerners and missionaries and the vengeful violence of the Boxers in ways that force the reader to confront the ethical and moral issues inherent in both. And infused in both stories are subtle and not-so-subtle thoughts on gender, class and internal cultural conflicts.

Yang deftly poses parallel conflicts about identity and faith and patriotism, while seeming to return to questions of compassion again and again. Both Little Bao and Vabiana are struggling with who they are and who they are meant to be – near-universal struggles for adolescents across time and place — but they are struggling within a web of cultural context and conflict which seems to steer them to do “wrong” despite their earnest desires to do what is “right.“

Even more extraordinary, the two-volume set explores a specific time in history from dueling non-Western perspectives, but many of the conflicts and themes are relevant today, in both our domestic and international conflicts. Is violence, even murder, justified if you are defending your land, your home, your country? Is it justified to defend your faith? What place do women have in your society and in your faith? What role does vengeance play in our conflicts? What place does human compassion have in the hierarchy of patriotism and faith and cultural change? When confronted by another human being who is your enemy, do they stop being a human being first? Do you?

As works of art, both volumes use line and color to dramatize the places in the story where the reality of historical fact is influenced by mystical force. The vibrant war gods of the Boxers and the golden-hued Joan of Arc in Saints explore the parallel mystical inspirations the teen characters struggle to interpret in the otherwise less technicolor reality of their lives. Yang’s gifts for emotion and depth through illustration and pointed barb through caricature are put to good use in both Boxers and Saints, exploring the moments of truth and the moments of ridiculous in both movements and faiths.

Boxers and Saints can be a jumping off point for exploring the Boxer Rebellion in greater depth, can be used in talking about the cultural and religious roots inherent in modern conflicts, and can lead to discussions exploring compassion as a consideration often missing from our modern politics, policies and conflicts. Reading Boxers and Saints as companion stories can also be an exercise in examining conflict from multiple perspectives. Where these stories intersect, there are lessons to be learned that may well resonate for today’s teens grappling with who they are, what they believe, where they belong, and what means are justified in pursuing their desired ends. And, above all, they are a layered, enjoyable, worthwhile read.

While the two volumes stand alone as complete stories, together they tell a richer, more complex, more enlightening tale. Personally, I suggest reading Boxers first, then Saints, and then exploring the places where the stories intersect side-by-side.

1 comment for “Review: Boxers & Saints”