The experiences of child soldiers in various parts of Africa have been the subject of novels, memoirs, and even picture books in recent years. For adult and older teen readers, outstanding titles include Ishmael Beah’s memoir A Long Way Gone, Dave Eggers’ fictionalization of Valentino Achak Deng’s testimony in What Is the What, and Ahmadou Kourouma’s novel Allah Is Not Obliged. Brothers in Hope, by Mary Williams and R. Gregory Christie, presents the experience of the Lost Boys in Sudan for readers at the elementary school level.

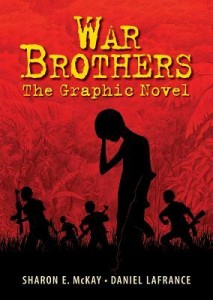

Sharon E. McKay and Daniel Lafrance’s War Brothers: The Graphic Novel portrays the experiences of four boys kidnapped into the Lord’s Resistance Army. Jacob and his friends Tony, Paul, and Norman are young teenagers in many ways not much different from the middle schoolers who are the principal audience for this book. Jacob and Tony are from the same well-to-do neighborhood in Gulu, a city in eastern Uganda where the Acholi people live. Their friend Paul from boarding school has spent his summer visiting family in New York City and arrives at the beginning of the new semester with swag from his trip. They are joined by Norman, a younger (and very homesick) boy who has skipped grades because of his academic ability. Jacob pledges to help Norman make his way through school.

Sharon E. McKay and Daniel Lafrance’s War Brothers: The Graphic Novel portrays the experiences of four boys kidnapped into the Lord’s Resistance Army. Jacob and his friends Tony, Paul, and Norman are young teenagers in many ways not much different from the middle schoolers who are the principal audience for this book. Jacob and Tony are from the same well-to-do neighborhood in Gulu, a city in eastern Uganda where the Acholi people live. Their friend Paul from boarding school has spent his summer visiting family in New York City and arrives at the beginning of the new semester with swag from his trip. They are joined by Norman, a younger (and very homesick) boy who has skipped grades because of his academic ability. Jacob pledges to help Norman make his way through school.

Almost immediately, guerrillas with the Lord’s Resistance Army overpower the new guards the students’ families have hired and kidnap the young students. The LRA, led by international war criminal Joseph Kony, claim to be Christians and Acholi nationalists, but they have violated the principles of Christianity and massacred thousands of Acholi people. At first, Jacob and his friends are treated relatively well because the guerrillas hope to ransom them for a large sum of money. When that falls through, they give the boys a choice: to become killers, or to work as slaves for whatever food and water they can forage after the soldiers have been fed. Tony becomes a child soldier, while the other three slowly starve and endure regular beatings. A former child soldier assigned to guard them is moved by Jacob’s loyalty to the younger Norman, and he gives them tips on how to escape, but new challenges greet them when they find themselves on the run in a wildlife refuge and later, when they return to Gulu but are shunned as war criminals by their neighbors.

The characters are composites of boys the authors met on a research trip to Uganda, where they visited former child soldiers who had undergone therapy. The story is gripping, and McKay does a superb job of connecting young readers to her characters and helping them to think about what they would have done in similar circumstances. Lafrance’s artwork establishes the setting and complements the text with familiar images—an “I Love NY” t-shirt, for instance—juxtaposed against the unimaginable horror that the boys endure. The format also allows the author and illustrator to cut away from the boys’ story to offer context, such as the U.N. indictment of Kony and the futile efforts of the boys’ fathers to raise the money to free them. Readers see that these are children of privilege, but in the end, none of their advantages can help them; ultimately, it is up to them to save themselves.

2 comments for “Kidnapped in Uganda: A Review of War Brothers”