The Fox felt the car slow before the boy did, as he felt everything first.

The Fox felt the car slow before the boy did, as he felt everything first.

So begins Sara Pennypacker’s middle grade novel Pax (Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins, February 2016), a book about many things, including the effects of war. Not some long ago past war fought by distant and unknown strangers. Not a here-and-now war fought somewhere far away. But a near future war fought in the characters’ own backyard, literally.

Twelve-year-old Peter lost his mother more than five years ago, shortly before he rescued an orphaned kit from the cold. He named the fox Pax. While his gruff and distant father allowed that Peter could keep the fox “for now,” Pax has become completely domesticated, and Peter’s closest companion.

In the opening line, the car that is slowing is the car taking Peter to his grandfather’s house because Peter’s father is off to fight in a war. It is a car that is slowing down because Peter’s father is about to force him to abandon Pax by the side of the road, more than a hundred miles from their home, because Peter’s grandfather won’t tolerate the fox as a pet. The chapter is told through Pax’s point of view, which serves to heighten the reader’s experience of the coming betrayal and Peter’s anguish. And that pain is magnified even more by the reader’s realization, maybe for young readers at the same time as Pax, that the boy isn’t playing a game when he tosses Pax’s favorite toy – a small, plastic soldier – into the woods. Because as Pax waits, Peter doesn’t come bounding after Pax to play. Instead, Pax hears two car doors slam. And by the time Pax returns with the toy to the side of the road, the car is driving away, leaving Pax in the wild for the first time since Peter rescued him.

What follows is part fable, part quest, told in alternating chapters from Peter and Pax’s points of views. Peter’s chapters follow him to his grandfather’s house, drowning in sadness and anger and guilt. But Peter quickly resolves to travel back to that place by the side of the road and save Pax once again. The journey on foot, alone, in the shadow of war, will be hard, but Peter is determined. It was wrong to leave Pax there.

Pax’s journey, once he realizes his boy is not coming back, is one of reclaiming his natural instincts and learning to live in the wild, meeting other foxes, and finding his way. A way back to the home he knew with Peter, where he is sure to find his boy.

They are both tested. They are both challenged and injured, and yet determined to find the other. They both have to learn to trust, others and themselves. Peter is aided by Vola, a reclusive woman dealing with her own ghosts of a past war. He, in turn, aids her in finding her way back to the world of the living. Pax is aided by a pair of young wild foxes, and he, in turn, aids them to survive threats from both the natural and human world.

While young readers may not focus too much on the nebulous coming war, more astute readers may pick up clues that this is a civil war of some nature, maybe about the control of water. But whether the reader thinks bigger thoughts about the causes of war, its effects are clear and ever-present. Peter is uprooted from his home and separated from his father, and from Pax, his closest relationship. Pax is thrown into the wild, to fend for himself in an unfamiliar and dangerous place. And as the story draws to a climax, the reader learns that the battle lines are being drawn near Peter’s home, in an area where Peter and Pax have played in happier times. And that the preparations for the coming war, namely land mines, are already killing non-human creatures and wreaking havoc on the land. The threat to Peter and other humans in this war is clear. But Pennypacker does an extraordinary thing through Pax’s chapters, placing front and center the often-ignored effects of war on animals and natural habitats.

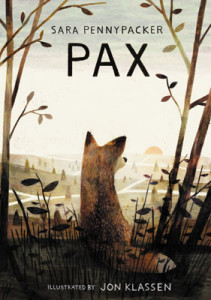

All of the human characters are well developed, believable, and rich in detail. Peter is brave, but age-appropriately shortsighted as to the threats he will face. Vola is eccentric, but she is also a manifestation of the long-term effects war may have on those who fight. But it is the world of the foxes — drawn with fascinating detail, exploring how they communicate and interpret the world around them — that shines. Readers will ache and cheer for the boy and his fox, even as it becomes clear that their relationship has been changed, too. And the written story is complimented by Jon Klassen’s beautiful and expressive illustrations.

Readers of all ages will find plenty of avenues to engage with Pax, and it is a highly discussable book, whether the conversations focus on topics such as family and love, grief and healing, or the effects of war. Some readers, young and old, may be most interested in the natural world of the foxes.

1 comment for “Review: Pax by Sara Pennypacker”