In 1943, in the middle of the Second World War, an American diplomat nearly loses the microfilmed score of a symphony, and millions of lives hang in the balance. Why?

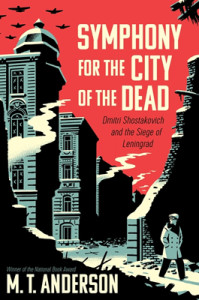

This fascinating vignette begins M.T. Anderson’s stunning nonfiction work Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad (Candlewick, 2015). Anderson creates a symphony of his own, interweaving music, biography, and history to explore the origins, composition and repercussions of this work of art, produced under the most challenging of conditions. Readers come to see that the survival of both Shostakovich and his Seventh Symphony was no less than a miracle.

This fascinating vignette begins M.T. Anderson’s stunning nonfiction work Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad (Candlewick, 2015). Anderson creates a symphony of his own, interweaving music, biography, and history to explore the origins, composition and repercussions of this work of art, produced under the most challenging of conditions. Readers come to see that the survival of both Shostakovich and his Seventh Symphony was no less than a miracle.

Before the war, before the rise of Joseph Stalin, before the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Shostakovich was a musically gifted middle class youngster growing up in a city once called St. Petersburg, then renamed Petrograd, and after the revolution once again renamed to honor the country’s new leader, Lenin. In the heady early years of the revolution, Shostakovich and other artists—musicians, visual artists, and writers—were able to experiment freely, a privilege for which they paid dearly once Stalin came to power and imposed Socialist Realism as the only approved style. Most of Shostakovich’s colleagues perished in the purges, as did his friends in the military who complained that Stalin’s retrograde views of warfare left the country unprepared against a rapidly militarizing Germany under Hitler. Once Hitler betrayed Stalin and invaded the Soviet Union, Shostakovich and his family were trapped in their besieged city, where the composer began to write his Seventh Symphony. The tale of how he and his immediate family were smuggled out of the starving to finish the symphony, worried about their friends and extended family still trapped there, is alone worth the price of the book.

Vivid language brings the music to life on the page. (Readers will probably want to listen to the symphony in the background, as I did.) Well-chosen historical photos show the ebullience of pre-Stalinist art and the grimness of life both under Stalin and during the almost three-year siege. The book reminds readers of how many Soviet citizens made the ultimate sacrifice to defeat Hitler, challenging our ethnocentric view of the war. For those who cannot imagine a work of art changing anything, Anderson convincingly shows why Shostakovich’s symphony meant so much to Russians—including musicians in Leningrad who performed it in public only hours before they died of starvation—and to Americans during the war who had little reason to contribute to relief efforts for people far away and “different” culturally and ideologically. But a brilliant work of music closed the gap and reminded people of our common suffering and our common humanity.