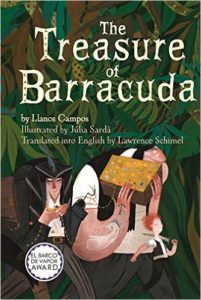

One of the best things about children’s books in translation is that they provide a window into what other countries publish—different artistic styles in illustrated books, different senses of humor, what constitutes a happy ending, and more. This is certainly true of The Treasure of Barracuda, a pirate tale for middle grade readers by Spanish author Llanos Campos, illustrated by Italian artist Júlia Sardà, translated by Lawrence Schimel, and published by Little Pickle Press.

One of the best things about children’s books in translation is that they provide a window into what other countries publish—different artistic styles in illustrated books, different senses of humor, what constitutes a happy ending, and more. This is certainly true of The Treasure of Barracuda, a pirate tale for middle grade readers by Spanish author Llanos Campos, illustrated by Italian artist Júlia Sardà, translated by Lawrence Schimel, and published by Little Pickle Press.

Pirate stories are universally popular, and this one comes with a twist. There’s the didacticism typical of Spanish publishing, but the author and illustrator wrap the message in so much absurd humor that readers don’t mind the preaching. In fact, it becomes a source of humor in itself, a metafictional wink-wink at didactic children’s books.

Eleven-year-old Sparks, a seventeenth century (or thereabouts) orphan is part of the motley 53-man crew of the Southern Cross, a pirate ship captained by the mercurial Barracuda. Barracuda seeks the treasure of the now-deceased legendary pirate Phineas Krane, who roamed the Caribbean, but when the crew digs at the marked spot, all they find is a book: Krane’s memoir. While Barracuda rages, Two Molars, the only crewman who knows his letters, starts teaching everyone else what those strange letters mean. Some learn faster than others, but within weeks, the Southern Cross crew can read! They discover many of Krane’s secrets, the location of new treasures, and the ominous threats of rival Fung Tao and his men from faraway China. Barracuda himself avoids being cheated while trying to sell booty. Soon, however, the pirates must hide their new-found literacy and knowledge that has come from it, lest they draw the envy of less lettered but heavily armed enemies.

The pirates and their enemies come from a variety of places in Europe and Asia, and the nationalities, like everything else in the book, are cartoon-like and played for laughs. Being aware of popular humor from other countries also means being aware of stereotypes, and translators are torn between faithfulness to the original and the sensibilities of readers in the new language. So it is for the “mysterious” and “fearsome” Fung Tao and his dragon coffer, along with a problematic illustration of him smoking a pipe made to look like an opium pipe (in fact, the British didn’t begin large scale imports of opium to China until the late eighteenth century). Would this be a problem for the more diverse readers of the United States, in comparison to their Spanish peers? If we want our young people to be aware of other cultures and literary traditions, to move confidently as global citizens, we should expose them to the world, its stories and humor, and help them develop the critical skills to put cartoonish humor and problematic portrayals from other lands in perspective.