Guest post by Padma Venkatraman

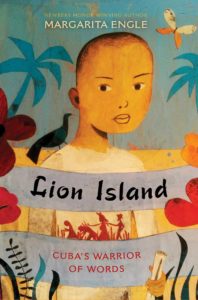

LION ISLAND: CUBA’S WARRIOR OF WORDS

By Margarita Engle

2016

Atheneum Books, Simon and Schuster

How lucky we are to have a writer like Margarita Engle in our midst, someone who dedicates her time and energy to bringing alive another culture and resurrecting bygone eras! Just as Linda Sue Park has created so many marvelous books that draw on her cultural heritage, Engle has created yet another wonderful book that draws on hers. How grateful I feel for authors like Engle and Park, whose books allow us to travel in time and place, for, by doing so, we broaden our understanding of our world’s history and our shared humanity.

I don’t have any knowledge of Cuban history. I can’t attest to the accuracy of the historical portrayal – except to say the author’s note provides evidence of Engle’s scrupulous efforts to research the period. What I can speak to is the trust one feels as soon as one reads the first poem – the assurance that one is in the presence of a skilled, honest and passionate writer.

As with her previous verse novels, Engle’s language is lyrical and evocative, spare but by no means sparse. With her amazing ability to pare down words, hone in on character and distill emotion, Engle has created yet another unforgettable story.

LION ISLAND is inspired by the life of a real person: Antonia Chuffat, a young Cuban of Chinese and African ancestry, who became a champion of civil rights, fighting first, for the freedom of Chinese indentured servants (which we see in this novel) and then, later, speaking up for African Cuban community (which we don’t see in the novel, but the author mentions in her note). There other actual historical figures that Engle brings to life, and the “major events described in LION ISLAND are factual” although the author has, of course, imagined details.

Engle has also, as with her many previous historical verse novels, created compelling fictional characters. Most compelling among them is Fan, a young woman who is Chinese and a talented singer. Fan, and her twin brother, Wing, are refugees from California, who left to escape the anti-Asian riots and lynchings – a potent reminder that there have been times when our nation was place from which people sought to flee injustice; that our nation has not always been a safe, egalitarian haven to which refugees flee. When Fan decides to defy her father and work at “el teatro chino”, Wing, Fan and Antonio find themselves able to battle the injustice around them, in their own quiet way.

A subtle theme that runs through the novel, that I found particularly interesting (perhaps because it is a theme that runs through my debut novel, CLIMBING THE STAIRS), is the question of violence versus nonviolence. Antonio is impressed and convinced of the “POWER in words”, whereas Wing has conflicting feelings and a strong desire, driven in part by impatience, in part by a longing to avenge the violence his family fled from. Fan bemoans the fact that her twin “…imagines that new violence can destroy/our old sorrows.” Antonio falls in love with Fan, but she does not reciprocate his feelings. Yet, despite these tensions, the three work together to hide runaways and help them get to safety.

The book begins with a short historical note, to help orient the reader, and is then divided into seven sections. Beginning in 1871, with Antonio a hesitant twelve year old, its ends in 1878, with Antonio a confident, capable and courageous young man.

While the brutality of indentured servitude is not depicted first hand, as it is outside the scope of this story, Engle’s target audience of middle-grade readers will hear powerful testimonies in the section “Listeners.” For example, in the verse entitled My Ghost Story, we hear from an indentured servant whose lives “…like an invisible spirit,/ followed by shrieking crows/ and howling wind,/ knowing that I could be whipped/ just like my friend, who bled to death/ from many/ narrow/ wounds.” In this compelling section, Antonio visits the fields where the indentured servants are forced to work, so that he can listen to and record their narratives. This section is filled with poems “inspired by real pleas for freedom” – which, I was delighted to hear were, in fact, written in verse. If the eventual success of the actual pleas does not speak to the power of poetry, what does?

This is “the final volume” in Engle’s “loosely linked group of historical verse novels about the struggle against forced labor in nineteenth-century Cuba.” I can’t wait to read the next book this prolific and gifted author will produce – whether it’s a verse novel or a picture book.