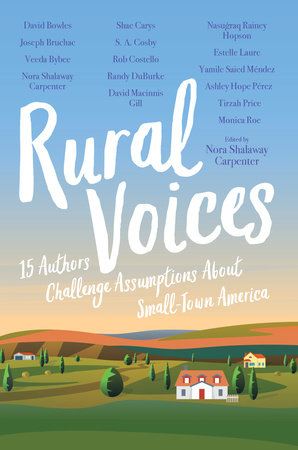

After the recent election, many commentators have focused on divisions between urban and rural residents and the far higher proportion of rural voters who chose right-wing authoritarian leaders. In fact, life in rural areas of the United States defies easy categorization in both past and present. The YA anthology Rural Voices: 15 Authors Challenge Assumptions About Small Town America, edited by Nora Shalaway Carpenter, portrays the experiences of teenagers living in rural areas, in towns of fewer than 10,000 people, and in doing so, presents their lives in all their diversity and complexity. The stories, poems, and essays are set in the present or recent past in Alaska, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Michigan, New Mexico, New York, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and West Virginia; the main characters include Black, Latinx, Asian American, Native American, queer, and disabled teens.

Leading off the collection is Monica Roe’s excellent story, “The (Unhealthy) Breakfast Club,” which presents a trio of scholarship students who meet early in the morning to do their homework at a McDonalds near a highway exit on the way to their private high school because they don’t have internet access at home. A white protagonist “counted out” because of his economic and family status asserts himself as well in David MacInnis Gill’s “Praise the Lord and Pass the Little Debbies,” which exposes the hypocrisy of a Christianity rooted in the Prosperity Gospel.

Other stories challenge the stereotype of rural residents as uniformly white. that rural residents are uniformly white. Again, the assumptions and stereotypes the characters confront are more about class than race. In S.A. Cosby’s “Whiskey and Champagne,” the wealthy boss who accuses the protagonist’s father of theft is also Black. In David Bowles’s short story in verse, “A Border Kid Comes of Age,” a Latinx teenager in South Texas is inspired by his elders’ stories of activism and resistance against dispossession and the Vietnam War. Yet other stories, such as Veeda Bybee’s “Fish and Fences” and Yamile Saied Méndez’s “Island Rodeo Queen,” show solidarity and generosity across racial, ethnic, and class lines.

We see also the dilemmas that queer teenagers face in small towns. For the protagonist and his boyfriend in Rob Costello’s “The Hole of Dark Kill Hollow,” it involves choices — to risk magic not to be gay, or to risk leaving their upstate New York town to be who they are. In Tirzah Price’s “Best in Show,” a series of mishaps on a girl’s first date with her crush leads to the possibility of coming out at the state fair, which has been the high point of her year ever since she was young. Life in small towns and on farms has no shortage of excitement and surprises, as the protagonist of Nora’s story “Close Enough” finds when a bull chases her and her friend up a tree.

This collection is an important step toward a more nuanced understanding of rural life among those who live in cities and suburbs, but it’s also for readers young and old who live in rural areas to see themselves in all their diversity. Everyone has stereotypes and assumptions that need to be challenged, including the prep-school classmates of the three Unhealthy Breakfast Club members, the small-town Black entrepreneur ignoring his own son’s problems, and the church leaders who cannot acknowledge the dignity and intelligence of those who question a doctrine that denies them God’s grace. Story by story, reader by reader, I hope Rural Voices can help undo the polarization that threatens the foundations of our democracy.