Six weeks ago, I took my first trip to the Occupy Wall Street encampment in Zuccotti Park. Since then, the numbers have grown in New York City, and the Occupy movement has spread to hundreds of other cities in the United States and around the world. Demonstrators have faced violence and arrest in numbers not seen in this country since the 1960s. The images of tear gas, dogs, mounted police, and demonstrators shot by rubber bullets and tear gas canisters evoke the days of the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War protests.

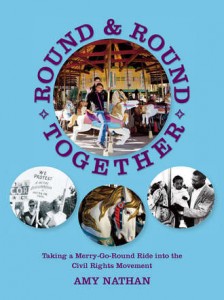

As the participants in the Occupy movement seek to create a more just economic system and politics that are truly democratic and participatory, they can look to the past for direction in terms of which strategies and tactics worked or didn’t work on the road to achieving their aims. A number of nonfiction titles on teens and the civil rights movement have appeared in recent years, among them Phillip Hoose’s Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice and Elizabeth Partridge’s Marching For Freedom: Walk Together Children and Don’t You Grow Weary, both winners of major awards and distinctions. While they highlight the participation of young people, they do not address the efficacy of methods the participants used over the course of the civil rights struggle. In her new title, Round & Round Together: Taking a Merry-Go-Round Ride into the Civil Rights Movement, Amy Nathan uses the effort to integrate a single business in Baltimore, Maryland, to address the specific ways activists confronted injustice and the results of these efforts over time.

The author, a native Baltimorean, describes the 16-year struggle, from 1947 to 1963, to open the city’s most popular amusement park, Gwynn Oak Park, to blacks. Built in the 1890s, Gwynn Oak was always a whites-only park, in keeping with Jim Crow practices established throughout the South and the border states in that era. Through oral history interviews and other primary sources such as the (Baltimore) Afro-American, she portrays the impact on the city’s black citizens of seeing advertisements and other promotions for a park they were not allowed to enter. Nathan explores what worked and what didn’t work over the years in terms of strategies and tactics, as well as how civil rights struggles in other areas of the country affected Baltimore and the contributions that Baltimore’s activists made to the movement. In the end, Gwynn Oak was one of the city’s last businesses to welcome black customers, and Nathan assesses the relative impact of pickets, demonstrations, non-violent civil disobedience, mass arrests, “jail-no bail,” and religious leaders’ efforts to negotiate with Gwynn Oak’s owners and local and state leaders. Today, the carousel from the park—which survived the destruction of Hurricane Agnes that claimed the other amusements—sits on the National Mall in front of the Smithsonian Institution and as the Carousel on the Mall is enjoyed by riders of all races and nationalities.

The author, a native Baltimorean, describes the 16-year struggle, from 1947 to 1963, to open the city’s most popular amusement park, Gwynn Oak Park, to blacks. Built in the 1890s, Gwynn Oak was always a whites-only park, in keeping with Jim Crow practices established throughout the South and the border states in that era. Through oral history interviews and other primary sources such as the (Baltimore) Afro-American, she portrays the impact on the city’s black citizens of seeing advertisements and other promotions for a park they were not allowed to enter. Nathan explores what worked and what didn’t work over the years in terms of strategies and tactics, as well as how civil rights struggles in other areas of the country affected Baltimore and the contributions that Baltimore’s activists made to the movement. In the end, Gwynn Oak was one of the city’s last businesses to welcome black customers, and Nathan assesses the relative impact of pickets, demonstrations, non-violent civil disobedience, mass arrests, “jail-no bail,” and religious leaders’ efforts to negotiate with Gwynn Oak’s owners and local and state leaders. Today, the carousel from the park—which survived the destruction of Hurricane Agnes that claimed the other amusements—sits on the National Mall in front of the Smithsonian Institution and as the Carousel on the Mall is enjoyed by riders of all races and nationalities.

What makes Nathan’s account of this moment in civil rights history especially valuable are two things: first, her seamless weaving of the larger context of both Jim Crow’s indignities large and small and the direction of the civil rights movement as a whole, and second, her unwavering focus on what ultimately made the campaign to integrate the amusement park a success. The former makes this case study a revealing microcosm of the movement. The latter makes it a useful primer for young activists today.

The publisher of Round & Round Together is the Philadelphia-based small press Paul Dry Books, which specializes in nonfiction and memoir and is seeking to expand its publishing program for young readers. Nathan’s book is a strong entry and a powerful argument for looking outside the publishing “box.”

1 comment for “What History Can Teach the Occupiers: A Review of Round & Round Together”