Reading Ann Angel’s review of Carlos Eire’s memoir Learning to Die in Miami—and then reading the book itself—got me thinking about the crossover genre, books originally published for adults that have found a wide audience of teens, or books published for teens or younger children that have become adult favorites. My own Gringolandia first came out as a YA novel but is now showing up in college classes and on bookstore shelves in the adult section. In various stops on my blog tours several years ago, I participated in thoughtful discussions on why the novel was published as young adult rather than adult, as its teen protagonists moved almost exclusively in an adult world, with the high stakes reflected in this exchange between Daniel and his girlfriend after they’ve entered a brutal dictatorship (Chile under Pinochet) with forged documents:

With her finger, Courtney traces the map in the guidebook. “We have to be back before curfew.” She flips to the previous page and says, “It’s kind of like the government is our mother.”

“Yeah. Except she doesn’t ground you when you miss it. She shoots you.” (208)

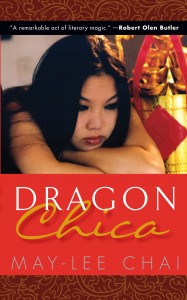

The same high stakes characterize May-lee Chai’s Dragon Chica, published by indie press GemmaMedia as an adult novel but of interest to teen readers who appreciated An Na’s award-winning YA novel A Step from Heaven. Like A Step from Heaven, Dragon Chica is told in chronological vignettes that end with the Asian-American protagonist about to leave for college after a series of crises that threaten to divide her family forever.

The same high stakes characterize May-lee Chai’s Dragon Chica, published by indie press GemmaMedia as an adult novel but of interest to teen readers who appreciated An Na’s award-winning YA novel A Step from Heaven. Like A Step from Heaven, Dragon Chica is told in chronological vignettes that end with the Asian-American protagonist about to leave for college after a series of crises that threaten to divide her family forever.

Dragon Chica doesn’t begin in the old country, however, but in Dallas, Texas in the 1980’s, where then-12-year-old Nea’s mother has abruptly taken the family and from where they will leave just as abruptly. Nea’s mother is accustomed to fleeing under cover of night. The family—including Nea, her older sister, her younger brother, and younger twin sisters—have escaped Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge for asylum in the United States following the death of the children’s father in the camps. Leaving Dallas, the family arrives in Nebraska, where Nea’s aunt and uncle own a struggling Chinese restaurant. Once prosperous, Aunt and Uncle have found few customers and much prejudice in their small town. Ultimately, Uncle will sell both the restaurant and Nea’s older sister’s hand in marriage to a wealthy and somewhat sketchy former business associate who is establishing a chain of Chinese restaurants in the Midwest.

In contrast to her submissive older sister, Nea quickly embraces the ways of the United States and of every place she has lived—hence the tough “Dragon Chica” image (and Spanish accent) she has adopted from her months in Dallas. She chafes against a family that sees her only for the labor she can provide and a community that refuses to accept her as an equal. She wonders why her mother, aunt, and uncle don’t treat her the same way that they treat her siblings, but her memories of the dark days of the Khmer Rouge and her life before are dim and reflect the trauma of having survived the genocide.

Dragon Chica is a powerful and gripping story that offers a model of strength and survival to young people going through difficult times. Nea is far from a stereotypical “good girl” and her toughness and willingness to stand up to injustice add to her appeal. Although published as an adult title—and certainly of interest to adult readers—Dragon Chica belongs in teen collections. It is a story that transcends age, ethnicity, and immigration experience to cast light on all of us struggling against the forces that constrain our lives.

1 comment for “Crossover Dreams: A Review of Dragon Chica”