On Saturday I journeyed to Zuccotti Plaza in New York City, site of the two-week-old Occupy Wall Street action. Occupy Wall Street began with a sit-in by a small group of college students—some still in their teens, others just beyond them. They have seen their prospects diminish while the wealthiest one percent prospers in the current recession. Several told me about parents laid off and unable to find new jobs—experienced, dedicated workers thrown away like garbage by companies that refuse to hire anyone currently jobless or of an age in which they’d require living wages or generate additional costs to the company health plan. Two of the laid-off mothers were teachers in states where budgets have been balanced by cutting school funding and social programs while giving tax cuts to the super-rich. I was moved by these young peoples’ concern for their parents and for the fate of the country as a whole.

In Gringolandia I wrote about a teenager who helps build a barricade and set it on fire out of concern for his father, imprisoned and tortured under his country’s dictatorship, and for his girlfriend, at a human rights demonstration imperiled by troops the barricade is designed to block. Presenting young people who join a resistance movement against oppression is bound to stir up controversy; it is far easier to portray children forced to fight by a tyrannical regime or violent gangs. However, always depicting children and youth as passive victims of oppression is ultimately disempowering to young readers who may themselves have to stand up to bullies in their schools and, perhaps one day, to systematic unfairness in their workplace or society. They will need to understand how to engage in nonviolent resistance and to defend themselves while maintaining respect for the humanity of the bully or oppressor. For instance, the barricade in Gringolandia is designed to prevent an act of violence, an attack by the army on a nonviolent women’s march, and protagonist Daniel later body-checks a soldier to prevent an injury to his girlfriend.

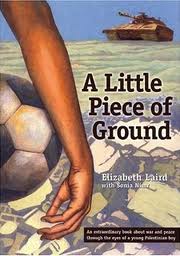

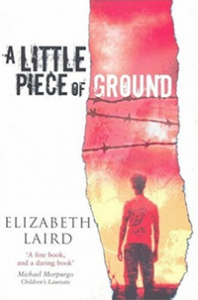

This theme of children and teenagers standing up to oppression appears in one of the most controversial middle grade novels of the last decade, Elizabeth Laird and Sonia Nimr’s A Little Piece of Ground. This novel does not regularly turn up on banned-books lists, however, because the censorship occurred even before A Little Piece of Ground was published. Brought out in the U.K. by Macmillan in 2003, the novel failed to find a major publisher in the United States or Canada and ended up with the tiny nonprofit alternative press Haymarket Books, which published it in 2006. Without the backing of a major imprint, the novel received few reviews and little presence in libraries despite its success and author Laird’s prominence overseas.

This theme of children and teenagers standing up to oppression appears in one of the most controversial middle grade novels of the last decade, Elizabeth Laird and Sonia Nimr’s A Little Piece of Ground. This novel does not regularly turn up on banned-books lists, however, because the censorship occurred even before A Little Piece of Ground was published. Brought out in the U.K. by Macmillan in 2003, the novel failed to find a major publisher in the United States or Canada and ended up with the tiny nonprofit alternative press Haymarket Books, which published it in 2006. Without the backing of a major imprint, the novel received few reviews and little presence in libraries despite its success and author Laird’s prominence overseas.

The main character of A Little Piece of Ground, 12-year-old Karim, lives in the city of Ramallah, on the Israeli-occupied West Bank. He longs to play soccer, but is cooped up with his parents and three siblings in a small apartment due to the endless curfews. When the curfew temporarily ends, he meets Hopper, a youngster from a refugee camp who goes to his school. Despite his parents’ prohibition against Karim’s playing with refugee kids—who they feel are of a lower social class and more apt to throw stones or otherwise provoke Israeli soldiers, which would lead to the punishment of the entire family—the two boys clear a rubble-filled lot near the camp to make a soccer field. While a group of boys are playing on the newly cleared field, the curfew is suddenly reimposed. After throwing stones at the tanks, the other boys run away. Karim turns his ankle while fleeing and seeks safety in an abandoned car, where for days he is trapped and in mortal danger.

Told through vivid third-person narrative from Karim’s point of view, the novel benefits from well-developed characters (especially the secondary characters), ample humor, realistic teenage banter, and a well-drawn setting. Although this is a political book, it is not heavy-handed because of the complex characters. The Palestinian Arabs do not appear as all good, nor the Israeli soldiers as entirely evil. Some of the soldiers treat the children with compassion, and readers see Arabs who discriminate against other Arabs—sometimes over religion (Karim and Hopper are Muslim; Karim’s other best friend, Joni, is Christian) but more often over issues of social class and connections. The prolific and popular British author Laird and her Palestinian collaborator draw readers into the dilemmas of real people living in difficult circumstances.

As Banned Books Week comes to a close, we should call attention not only to those books regularly removed from schools and libraries but also to those books that never get there because they don’t get the backing of a major publisher. This review site and others like it have the power to find and publicize those books, many of which offer perspectives and raise questions not available anywhere else. A Little Piece of Ground is one of those books.

2 comments for “Children as Combatants: Young People Standing Up”