Several outstanding nonfiction books for youth published in the last few years have told the story of the civil rights movement in Birmingham, Alabama, a city notorious even in the South for its resistance to change and the amount of violence leveled against activists. Larry Dane Brimner has won numerous accolades for Birmingham Sunday (2010) the story of the four girls killed in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963, and Black & White: The Confrontation Between Reverend Fred L. Shuttlesworth and Eugene “Bull” Connor (2011), just named to the Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Award honor list.

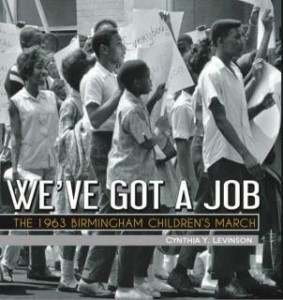

While Brimner’s most recent title focuses on the leaders on both sides, We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March by Cynthia Y. Levinson (Peachtree, 2012) tells the civil rights story through the aspirations and actions of Birmingham’s young people. It, too, is worthy of an award, as it builds the reader’s emotional attachment to her four principal protagonists the way a novel would for its characters.

While Brimner’s most recent title focuses on the leaders on both sides, We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March by Cynthia Y. Levinson (Peachtree, 2012) tells the civil rights story through the aspirations and actions of Birmingham’s young people. It, too, is worthy of an award, as it builds the reader’s emotional attachment to her four principal protagonists the way a novel would for its characters.

Levinson selects young people who represented different backgrounds and reasons for becoming civil rights activists. Audrey Hendricks, at age nine the youngest person to be arrested for participating in the children’s march, was the daughter of longtime activists and friends of Rev. Shuttlesworth. In fact before the march Audrey’s parents bought her a new toy to help pass the time in jail. Washington Booker III came from a tough working-class neighborhood and was no stranger to police violence; he had been arrested previously for truancy and minor lawbreaking. In the course of the 1963 civil rights campaign, he and other working-class black teenagers would reject the organization and discipline of the mostly middle class leaders, choosing not to march peacefully but to throw rocks at police. However, he also observed the strength of the marchers and over time adopted their goals and methods. The son of one of the few black doctors in town, James Stewart defied his parents’ admonitions to stay out of the conflict. While in jail, he became ill and his worried parents bailed him out even though the hundreds of arrested children and teens pledged to remain in jail without bail to bring about the collapse of the local criminal justice system. Once free, however, he found a way to support his fellow marchers with the blessing of his parents. Nineteen-year-old Arnetta Streeter had already proven herself a leader in various organizations in high school and college, and she and her friends played a central role in organizing and leading the march and providing support to others.

Levinson’s gripping account challenges much of the civil rights orthodoxy. Not all efforts remained peaceful, as Wash’s occasional rock-throwing shows. Rev. Shuttlesworth and Martin Luther King, Jr., who spent many days in Birmiingham (ten of them in jail in solitary confinement where he wrote his famous “Letters from the Birmingham Jail”) had to work hard to keep tempers from boiling over. Anything that could potentially be used as a weapon was confiscated before each march, sit-in, or other action. The leaders were effective in calming down situations so that the images the country saw of Birmingham were uniformly those of violence carried out by the police and the Ku Klux Klan (and by policemen who were also members of the Klan). Readers also see that the movement in Birmingham nearly failed. Because the adults of the black community feared losing their jobs if they attended a meeting or march, the numbers of participants dwindled to almost zero in the spring of 1963, before Shuttlesworth and a youth minister named James Bevel decided to mobilize young people. This, however, was a controversial strategy, because many of the city’s black elders objected to the idea of children being put—or putting themselves—at risk. While hundreds of children suffered at the hands of authorities—jailed under deplorable conditions, attacked by dogs, injured by water cannons—they also felt empowered. They saw that they could control their own destiny and end a system of oppression that afflicted generations before them.

Young readers of We’ve Got a Job will come away from this book with a sense of hope, that idealistic young people can triumph over opponents who may have appeared stronger but who lacked the strength of a moral position.

3 comments for “We’ve Got a Job”