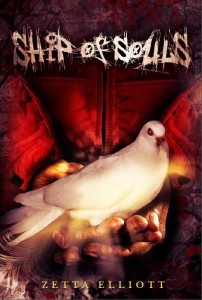

Tomorrow, Saturday, March 3 marks the official launch of Ship of Souls. If you’re in the New York City area, the “Book-day” event will take place at the site of the African Burial Ground National Monument, 290 Broadway in Manhattan between Duane and Reade Streets from 1-3 pm. Although I can’t be there, I was able to interview author Zetta Elliott and offer some of her thoughts on this book, her other writing, and the publishing process. Thanks, Zetta!

Your first novel, Bird, is a contemporary realistic story, but since then, you’ve written two time-travel fantasies. What attracted you to this genre?

When I look at my work, I definitely see a fantasy vein running through many of my stories. At the end of Bird, Uncle Son recalls the story of the flying Africans. I call this “Afro-urban magic”—I use African-derived spiritual practices or concepts to infuse a magical element into otherwise realistic fiction. I was always drawn to magic as a child, but those books (The Phoenix and the Carpet, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) never featured children who looked like me, and the white children always had to leave the city for something special to happen. Now I try to write magical stories that are set in the city with a cast of urban kids to show that magic can happen to anyone anywhere.

When I look at my work, I definitely see a fantasy vein running through many of my stories. At the end of Bird, Uncle Son recalls the story of the flying Africans. I call this “Afro-urban magic”—I use African-derived spiritual practices or concepts to infuse a magical element into otherwise realistic fiction. I was always drawn to magic as a child, but those books (The Phoenix and the Carpet, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) never featured children who looked like me, and the white children always had to leave the city for something special to happen. Now I try to write magical stories that are set in the city with a cast of urban kids to show that magic can happen to anyone anywhere.

In A Wish After Midnight, Genna thinks she’d rather be anywhere than where she is now–until she’s transported to Civil War Brooklyn and believed to be a fugitive from slavery. How do you see Dmitri’s journey to the African Burial Ground relating to his present-day situation?

I think D is a lot like the dead in Ship of Souls—they’re in a state of limbo, really, stuck in time. The souls of the enslaved are seeking peace and are waiting for release. The ghosts of the Revolutionary War soldiers would rather cling to life and the site where they died—they haven’t truly embraced death but also can’t accept that they’ll never live as fully human again. D has lost the one person who mattered most to him; without his mother, he finds it hard to plan for the future and he’s wary of forming new attachments. This makes him serviceable as a host for Nuru and D wants to have a sense of purpose, but his heart still yearns for the connection he finds with Nyla and Keem. I think “home” is a central concept in SoS; everyone is seeking sanctuary, a place of rest, a place to belong. D initially wants an “out” from his rather bleak life, but the lesson he learns from Nuru is that he has to work to build community. D has to open himself to the possibility of love despite his fear of abandonment. Like the souls of the dead, he has to hold on and have faith…

Who do you see as your readership for Ship of Souls? How did you write this novel to appeal to that readership? To keep Ship of Souls shorter than most fantasies, what did you have to leave out?

I definitely had reluctant readers in mind, but I also know how hungry urban kids are for multicultural speculative fiction. I teach so I have to be realistic about the kind of projects I can complete during the academic year. I knew  from the outset that SoS would be a novella; I’m still working on Judah’s Tale, the sequel to A Wish After Midnight, and it’s hard to find enough dream time, research time, and writing time to finish a 100K-word novel. So I knew that I was going to write a novella, that it would be fast-paced, involve fewer characters, and the action would take place over 2-3 days. I think reluctant readers—and boys especially—need to feel confident when they pick up a book; they need to believe they can reach the end, and they need to have fun getting there! So to keep the plot moving, I left out a lot of excess detail—I included only what I felt was essential, and then went back and added a few extra details. There are two more books to follow, so I also knew that loose ends could be tied up in the companion books. Nyla’s story will be next, and then Keem will have his own book, too.

from the outset that SoS would be a novella; I’m still working on Judah’s Tale, the sequel to A Wish After Midnight, and it’s hard to find enough dream time, research time, and writing time to finish a 100K-word novel. So I knew that I was going to write a novella, that it would be fast-paced, involve fewer characters, and the action would take place over 2-3 days. I think reluctant readers—and boys especially—need to feel confident when they pick up a book; they need to believe they can reach the end, and they need to have fun getting there! So to keep the plot moving, I left out a lot of excess detail—I included only what I felt was essential, and then went back and added a few extra details. There are two more books to follow, so I also knew that loose ends could be tied up in the companion books. Nyla’s story will be next, and then Keem will have his own book, too.

Recent articles have decried the impact of Amazon Publishing on bookstores–both chains and independents–and on the other large corporate publishers. Defenders of Amazon like you and Debby Dahl Edwardson have pointed out that the large bookstore chains, many independent stores, and corporate publishing have been less than supportive of books by and about people of color. Do you feel that Amazon gives authors of color a fairer shake than other publishers and booksellers? How has Amazon succeeded in selling books by and about people of color when other places have not?

As a giant e-retailer, Amazon can stock just about anything. That’s the primary advantage for a writer like me—people around the world, if they have access to a computer, can have access to my books. There isn’t the same level of curation, and many people assume that we need that curation to ensure that only “the best books” make it onto the shelves and into our hands. But a tiny handful of people, acting as gatekeepers, shouldn’t have that much power. They can’t meet the needs of the diverse society in which we live. Many bookstores are refusing to stock books published by Amazon, but those same stores never stocked Bird, an award-winning picture book published by a small multicultural press. They won’t stock my self-published titles—and it was Amazon who made self-publishing so easy (with CreateSpace). I understand the fear of domination, but the response from the publishing community should be INNOVATION. They aren’t even trying to compete by offering something comparable—or something wholly original. They’re just counting on the loyalty of consumers, even when many of those consumers (especially people of color) haven’t been served well by these presses and stores. I want a publishing community where readers, writers, and retailers have options. If stores don’t want to carry Ship of Souls and A Wish After Midnight, that’s their choice. But I only see that pushing readers right back to Amazon.com.