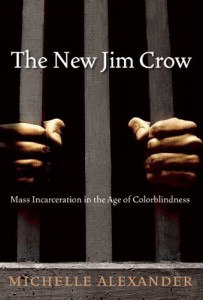

Last month I attended a local march to call for an investigation of the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin by a self-appointed neighborhood watch member in suburban Florida. At the Albany march, several of the speakers mentioned the bestselling book by Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Jim Crow is one of the most persuasive arguments that this country still has a long way to go in terms of race relations. Alexander examines the population of the country’s prisons and reveals that African Americans and Latinos are significantly more likely to end up in prison, and with longer sentences, than whites who commit the same offenses. This is particularly true for nonviolent drug offenders. Unfortunately, prisoners, parolees, and in many states ex-convicts who have paid their debts to society are unable to vote. Those with prison records generally cannot obtain decent employment, college scholarships, and housing. Like those subjected to the old Jim Crow laws in the South, they are disenfranchised, isolated from mainstream society, and forever limited in their life prospects. Discrimination in the criminal justice system affects convicts’ families, and the effects are intergenerational, as men are no longer available to support their families and raise their children, and brutalization of life in prison and limited opportunities thereafter leads to the sort of hopelessness that often manifests itself in substance abuse, domestic violence, and further criminal activity. In fact, a speaker addressed that issue at the rally, talking about how he survived prison and had to work at minimum-wage jobs to get his life back on track. He urged young people not to make the same mistakes he made, but along with personal choices, we as a society need to make sure that the law applies equally to all regardless of race or economic status.

Last month I attended a local march to call for an investigation of the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin by a self-appointed neighborhood watch member in suburban Florida. At the Albany march, several of the speakers mentioned the bestselling book by Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Jim Crow is one of the most persuasive arguments that this country still has a long way to go in terms of race relations. Alexander examines the population of the country’s prisons and reveals that African Americans and Latinos are significantly more likely to end up in prison, and with longer sentences, than whites who commit the same offenses. This is particularly true for nonviolent drug offenders. Unfortunately, prisoners, parolees, and in many states ex-convicts who have paid their debts to society are unable to vote. Those with prison records generally cannot obtain decent employment, college scholarships, and housing. Like those subjected to the old Jim Crow laws in the South, they are disenfranchised, isolated from mainstream society, and forever limited in their life prospects. Discrimination in the criminal justice system affects convicts’ families, and the effects are intergenerational, as men are no longer available to support their families and raise their children, and brutalization of life in prison and limited opportunities thereafter leads to the sort of hopelessness that often manifests itself in substance abuse, domestic violence, and further criminal activity. In fact, a speaker addressed that issue at the rally, talking about how he survived prison and had to work at minimum-wage jobs to get his life back on track. He urged young people not to make the same mistakes he made, but along with personal choices, we as a society need to make sure that the law applies equally to all regardless of race or economic status.

As I listened to these speakers and reread Alexander’s book, I thought of two YA novels I read recently with African- American characters trapped in the criminal justice system. Originally published in 2002 as an adult novel by a small press, Paul Volponi’s Rikers High reappeared in a revised version in 2010, published by Penguin. High school senior Martin Stokes is now known only as “Forty,” his prisoner number at Rikers Island, where he awaits trial for “steering”—telling someone, who turns out to be undercover police officer, where he can buy marijuana in Martin’s neighborhood. This is the kind of “crime” that would never be prosecuted in a white middle-class area but which serves to saddle countless young African-American men with jail time and criminal records. A series of mishaps have led Martin to languish in jail for five months, and following another two-week delay, he is inadvertently slashed in the face by another inmate. The injury leads him to be transferred to a different wing where inmates attend high school, and with the support of two caring teachers, Martin gains perspective on his situation and direction for his life.

American characters trapped in the criminal justice system. Originally published in 2002 as an adult novel by a small press, Paul Volponi’s Rikers High reappeared in a revised version in 2010, published by Penguin. High school senior Martin Stokes is now known only as “Forty,” his prisoner number at Rikers Island, where he awaits trial for “steering”—telling someone, who turns out to be undercover police officer, where he can buy marijuana in Martin’s neighborhood. This is the kind of “crime” that would never be prosecuted in a white middle-class area but which serves to saddle countless young African-American men with jail time and criminal records. A series of mishaps have led Martin to languish in jail for five months, and following another two-week delay, he is inadvertently slashed in the face by another inmate. The injury leads him to be transferred to a different wing where inmates attend high school, and with the support of two caring teachers, Martin gains perspective on his situation and direction for his life.

Volponi creates a sympathetic protagonist and seamlessly weaves into his first-person narrative insights into an unequal justice system that victimizes young black and Latino men, ruining their lives and by extension the lives of their families and communities. Using vivid details and pertinent metaphors, he builds a setting that serves as an obstacle course and a trap, one that threatens to ensnare permanently even the most well meaning of captives. Readers hope that Martin will not become one of those ensnared, as his father has been, and they also empathize with his bright, thoughtful, but very unlucky friend Sanchez whose terror at going to an adult prison upstate for a drug conviction leads to his suicide. When Martin looks out over the dozens of teenagers in his dorm, sees only black and brown faces, and wonders why that has to be the case, readers come to understand on a personal level the true significance of the “New Jim Crow.”

While Volponi’s novel focuses on the impact of an unjust justice system on the incarcerated individual, Coe Booth’s Bronxwood (Scholastic, 2011)—the sequel to her acclaimed 2007 novel Tyrell—portrays the effects of mass incarceration on the family and community. With his father in jail and his mother unable to take care of her two sons, Tyrell ends up living with friends in the Bronxwood housing project, and his beloved little brother, Troy, ends up in foster care—the last place Tyrell wants Troy to be. But Tyrell’s father is finally getting out of prison. On the one hand, Tyrell hopes his father’s presence will at last lead to the family’s reunification. On the other, Tyrell dreads his father’s violent rages, his demands for respect and obedience that he hasn’t earned, and the criminal activities in which he engages while working as a DJ. Tyrell appreciates the skills that his father has taught him, but he wants to DJ parties that won’t attract the police and get him locked up. Throughout the novel, Tyrell talks about getting “locked up” as a fact of life for people in his community, but something he wants to avoid. He values his freedom, but above all, he values his dignity and self-respect.

While Volponi’s novel focuses on the impact of an unjust justice system on the incarcerated individual, Coe Booth’s Bronxwood (Scholastic, 2011)—the sequel to her acclaimed 2007 novel Tyrell—portrays the effects of mass incarceration on the family and community. With his father in jail and his mother unable to take care of her two sons, Tyrell ends up living with friends in the Bronxwood housing project, and his beloved little brother, Troy, ends up in foster care—the last place Tyrell wants Troy to be. But Tyrell’s father is finally getting out of prison. On the one hand, Tyrell hopes his father’s presence will at last lead to the family’s reunification. On the other, Tyrell dreads his father’s violent rages, his demands for respect and obedience that he hasn’t earned, and the criminal activities in which he engages while working as a DJ. Tyrell appreciates the skills that his father has taught him, but he wants to DJ parties that won’t attract the police and get him locked up. Throughout the novel, Tyrell talks about getting “locked up” as a fact of life for people in his community, but something he wants to avoid. He values his freedom, but above all, he values his dignity and self-respect.

Not only does Tyrell have to avoid his father’s criminal activities, he has to avoid his friends’ marijuana business, even though he rents a room from them. His best friend, Cal, is being forced to do increasingly dangerous work, and Tyrell cannot make his parents become responsible enough to get Troy out of the foster home. In fact, his father’s experience in prison has so brutalized him that he refuses to cooperate with any authorities, including those seeking to help his family, and his anger and helplessness threaten to drive the entire family toward disaster.

While Alexander’s focus in The New Jim Crow is on the economic rather than the psychological consequences of mass incarceration, she does talk about the stigma of the “prison label.” However, the rage and impotence of Tyrell’s father in Bronxwood, and its impact on the rest of the family, drives that message home in a powerful way, as does Martin’s sense of entrapment among a sea of black and brown faces in Rikers High.

2 comments for “Prison Novels and the New Jim Crow”