In the early 1990s I reviewed a historical novel for young readers, part of a historical fiction series from an educational publisher, about an interracial friendship between two 12-year-old boys in Wilmington, North Carolina in 1898. In the story, a race riot by white citizens culminated in the overthrow of the local government, and the black child was forced to flee the city with his family, thus ending the friendship. Although I gave the book a good review, other reviewers criticized it for being unrealistic and untrue—basically saying things like that “didn’t happen here.”

In the early 1990s I reviewed a historical novel for young readers, part of a historical fiction series from an educational publisher, about an interracial friendship between two 12-year-old boys in Wilmington, North Carolina in 1898. In the story, a race riot by white citizens culminated in the overthrow of the local government, and the black child was forced to flee the city with his family, thus ending the friendship. Although I gave the book a good review, other reviewers criticized it for being unrealistic and untrue—basically saying things like that “didn’t happen here.”

Except that it did. Until 2000, the Wilmington race riot and coup remained a “hidden history,” talked about in family stories and covered in obscure books that disappeared almost as soon as they were published. In the mid 1900s, books and reports on similar massacres of black residents in the early twentieth century in Rosewood, Florida and Tulsa, Oklahoma prompted soul searching among Wilmington’s white residents and in 2000 North Carolina’s legislature established the Wilmington Race Riot Commission, which issued its report in 2006.

Until 1898 Wilmington served as a model of interracial peace and cooperation in the South. The city had a strong black middle class, and wealthy blacks lived alongside wealthy whites in the city’s poshest neighborhood. Blacks served in the city’s government as elected officials and high-ranking administrators. The Wilmington Daily Record was the state’s only black-owned daily, with a circulation throughout the Carolinas.

The violence in 1898 followed a state election that put white supremacists in power. Between six and 100 black residents died and more than 2000 were driven out of town, turning a majority-black city into a majority-white city. The mob forced the elected leadership of the city—both blacks and whites—to resign and leave town. The new all-white government, working hand in glove with the state government, imposed Jim Crow laws and measures such as literacy tests and poll taxes to disenfranchise black voters. The substantial amount of property owned by blacks (including blacks who stayed in town) was seized and redistributed to whites with connections to the new government.

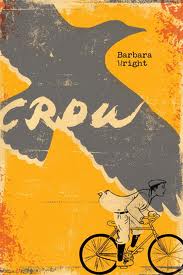

All of this is the historical context surrounding Barbara Wright’s recent novel for young readers, Crow (Random House, 2012). Eleven-year-old Moses Thomas is the son of the Wilmington Daily Record’s managing editor (it should be noted that he is a fictional character and not the newspaper’s real managing editor), who also serves in the city council. Jack Thomas is a strict parent—a graduate of historically black Howard University—and Moses worries that he is falling short of his father’s ambitions for him. Moses is also close to his mother’s mother, Boo Nanny, who grew up under slavery and believes in the old traditions that Jack Thomas disparages.

The beginning of the novel consists of a series of vignettes. Moses squabbles with his best friend, initiates a secret friendship with a white boy his age, and makes several efforts to obtain his heart’s desire—a bicycle. Along with his mother and Boo Nanny, he also discovers a dark family secret from the time before his people were free. As the seasons change from summer to fall, the narrative becomes more linear, and readers see that his parents’ effort to shelter Moses and give him a normal childhood has in fact put the youngster in greater danger. Everywhere they go in the weeks before the election, they see armed white supremacists, and Boo Nanny predicts bad times coming.

As the coup and massacre take place before Moses’s eyes, he loses faith in the goodness of the world and struggles to hold on to hope for his own future. The novel humanizes the experience of living under the system of racial subjugation known as Jim Crow, and shows the terror and violence used to establish this system. Imposing Jim Crow involved the murder of untold numbers of blacks and the taking away of people’s hard-earned property and status solely on the basis of their race. Wright offers a vivid portrayal of elections conducted under the threatening eye of armed militias—while Moses’s father says the then-segregationist Democrats won “fair and square” he refuses to acknowledge to his son the intimidating presence of the militias as well as the consequences of installing a state government that would not only fail to control the white supremacist mobs but would actively encourage them.