When it appeared in 2009, Kekla Magoon’s The Rock and the River took historical fiction about the African-American experience out of the “safe” terrain of the Underground Railroad and the Civil Rights Movement to an armed revolutionary organization that confronted racial and class-based oppression. In that novel, 13-year-old Sam Childs is torn between the nonviolent resistance supported by his father, a respected attorney and associate of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and his older brother’s support for the Black Panthers. As he is drawn to the Black Panthers, Sam is also drawn to Maxie Brown, a girl his age whose older brother, Raheem, is the best friend of Sam’s older brother. But while Sam comes from a well-to-do family, Maxie is working-class, the child of a single mother who lives in a run-down housing project.

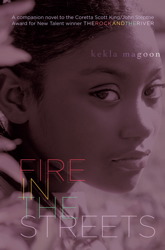

The well-deserved success of The Rock and the River prompted Magoon to write Fire in the Streets (Simon & Schuster, 2012), a companion novel from Maxie’s point of view—a wise choice since Maxie was an interesting and well-developed secondary character in the first book. Unlike Sam, who struggles with his decision to join the Panther organization in Chicago, Maxie is committed to the cause. She wants to be a full-fledged member—not someone who works in an office, but someone who carries a gun and knows how to use it, who goes out to the street to monitor the police for racism and brutality. But Maxie is 14 years old and must wait her turn. That is what Raheem tells her and also what Leroy Jackson, “the highest-up Panther I’ve ever personally met,” tells her. She thinks it’s unfair that Sam, who’s her age, gets to be a full-fledged Panther, even though she understands that Sam lost his beloved brother to a police shooting just months before.

The well-deserved success of The Rock and the River prompted Magoon to write Fire in the Streets (Simon & Schuster, 2012), a companion novel from Maxie’s point of view—a wise choice since Maxie was an interesting and well-developed secondary character in the first book. Unlike Sam, who struggles with his decision to join the Panther organization in Chicago, Maxie is committed to the cause. She wants to be a full-fledged member—not someone who works in an office, but someone who carries a gun and knows how to use it, who goes out to the street to monitor the police for racism and brutality. But Maxie is 14 years old and must wait her turn. That is what Raheem tells her and also what Leroy Jackson, “the highest-up Panther I’ve ever personally met,” tells her. She thinks it’s unfair that Sam, who’s her age, gets to be a full-fledged Panther, even though she understands that Sam lost his beloved brother to a police shooting just months before.

Maxie struggles with her feelings toward Sam—she wants to be friends (perhaps more than friends) but knows the death of his brother has changed him. She also struggles with her two best friends, as they seem to be growing in opposite directions, and she struggles in school because of dyslexia. Most of all, she struggles at home because her alcoholic mother keeps losing jobs and picking up sleazy boyfriends. When Raheem’s sense of responsibility for the family’s well-being threatens his political commitments, Maxie is caught in the middle, with a very serious decision to make.

Although written as a companion to an acclaimed earlier work, Fire in the Streets stands on its own. It explores the tension between middle-class and working-class African Americans as well as racial and class-based power dynamics, such as the scapegoating of Bobby Seale and the Panthers for the violence of the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. At a time when gun rights advocates call the Second Amendment the ultimate bulwark against government tyranny, Magoon explores a time and place in which being armed was also seen as a legitimate means of defense against what was then an overtly tyrannical police force and government. Fire in the Streets is a well-researched and compelling story that raises important issues for readers, young and old, today.

1 comment for “Maxie’s Turn: A Review of Fire in the Streets”