In Richmond, Virginia in 1867, 14-year-old Shadrach Weaver is awakened early and violently one morning. Federal soldiers beat him and carry away his older brother, Jeremiah, wanted for murder. The victim, George Nelson, is an itinerant teacher, a white man who has been setting up schools for recently freed blacks, and a specialist in reading disabilities to whom Shad, unbeknownst to his family and community, has been going for tutoring. In fact, Shad, who is white, is receiving lessons from Rachel, a black girl.

Two years after the end of the Civil War, known in Richmond as the War of Northern Aggression, the city remains in ruins and tensions run high. Federal soldiers patrol the streets and working-class whites complain that blacks get favored treatment for construction day jobs. Jeremiah has joined a secret organization to protect Confederate widows like his mother, and Shad signs up too, mainly to prove his manhood to his brother. Shad soon comes to realize that the organization, the Ku Klux Klan, terrorizes blacks and their white allies—and that nearly every white person in town, including his kindly grandfather who has taken Shad on as an apprentice tailor, is a member.

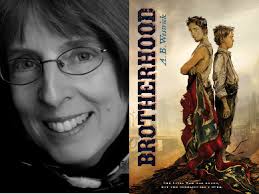

A. B. Westrick’s debut YA novel, Brotherhood (Viking, forthcoming in September) immerses readers in a community destroyed by war and far from any sort of reconciliation. The ongoing hostilities create plenty of conflict for a teenager who wants to both please everyone and do the right thing. Shad also wants a better future for himself, one in which people won’t laugh at him or take advantage of him because he cannot read. Westrick contrasts this sympathetic protagonist with a brother whose behavior crosses the line into sociopathic, to the extent that Shad hopes that the soldiers never let his brother out of jail after George Nelson’s death (in which Shad, too, played a role). Jeremiah does get out of jail, though, and the result is a gripping climax that sheds light not only on the history of Reconstruction but also on the war against terrorism today.

A. B. Westrick’s debut YA novel, Brotherhood (Viking, forthcoming in September) immerses readers in a community destroyed by war and far from any sort of reconciliation. The ongoing hostilities create plenty of conflict for a teenager who wants to both please everyone and do the right thing. Shad also wants a better future for himself, one in which people won’t laugh at him or take advantage of him because he cannot read. Westrick contrasts this sympathetic protagonist with a brother whose behavior crosses the line into sociopathic, to the extent that Shad hopes that the soldiers never let his brother out of jail after George Nelson’s death (in which Shad, too, played a role). Jeremiah does get out of jail, though, and the result is a gripping climax that sheds light not only on the history of Reconstruction but also on the war against terrorism today.

In an afterword, Westrick quotes a descendant of a Confederate soldier who says, “The United States treated Japan and Germany after World War II better than the North treated the South after the War Between the States.” The author does an outstanding job of getting into the heads of her vanquished Southern characters, in spite of the obvious risks of telling her story from the perspective of people who committed atrocities against others because of the color of their skin. Her research is impeccable, but it never overwhelms the story; in contrast, it shows us the world from the perspective of a young person torn between his community and his conscience.

1 comment for “Divided Loyalties: A Review of Brotherhood”