Young Adult novels often focus on the moment when a teen protagonist’s life is about to change — sometimes in small ways, and sometimes in large ways.

Young Adult novels often focus on the moment when a teen protagonist’s life is about to change — sometimes in small ways, and sometimes in large ways.

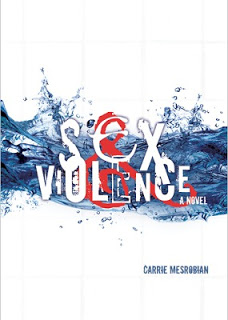

In the first chapter of Carrie Mesrobian’s Sex & Violence (Carolrhoda LAB, October 2013), we meet her main character Evan. Evan likes sex, sex without strings. He’s not interested in a relationship, or in even really knowing a girl beyond the sex. He barely sees girls as people. They are a means to an end.

There’s a girl named Farrah who likes him, but she would want to be wooed and romanced and then still probably wouldn’t go very far. And, besides, she has a crazy jealous ex-boyfriend who thinks he owns her. And then there is Farrah’s friend Collette. She’s Evan’s roommate’s ex, and Evan’s been warned away from her, too, but Collette pursues Evan and he can’t resist her or the easy sex.

Evan and Collette start hooking up in secret, and despite the risk, Evan likes what they do and it seems like he’s starting to actually like her, too. Evan is beginning to at least consider the double standard for guys and girls when it comes to sex, and the reader gets the sense Evan is starting to actually think about how Collette feels beyond what he can get from her.

In less capable hands, Evan would be entirely unlikeable. But Mesrobian has written Evan so that, despite all his bravado and behavior, there is more to him, a decent guy under all the self-protective and entitled crap. He’s real. He’s flawed. He’s a product of his world, where guys are expected to want and to pursue sex, where they are entitled to have their needs met, and girls are too often a conquest to be achieved.

Of course there is backstory to his worldview – his mother is dead, his father is distant and has a habit of parking Evan in different schools, in different places, while he’s off working. Evan’s reaction to impermanence is not to get too attached to anyone or anything. Especially girls. Evan barely even connects with the guys at his school. He classifies them as types, too — clichés, forces to deal with rather than friends. If the girls are potential objects of desire, the guys are potential sources of violence. Evan make take some risks in his pursuit of sex, but they are calculated, and he knows that if he chooses wrong and ends up with a girl who doesn’t let him just walk away, well, it’s only a matter of time before his father will move him again. Consequences don’t follow.

Until they do. Until Evan’s roommate finds out he’s been hooking up with Collette, and the roommate and Farrah’s jealous ex team up to teach Evan a lesson about touching what doesn’t “belong” to him. They ambush Evan in the hall bathroom after a shower, beating Evan so badly they nearly kill him. They rape Collette.

By the beginning of chapter two Evan is recovering in the hospital, and nothing will ever be the same again. He will never be the same again.

Evan’s father takes him to a family cabin on a lake in Minnesota to recover. If he is going to figure out how to relate to people again, he has to figure out who he is and how to live with that person – the person he is now, and the person he was before. He also has to recover physically and emotionally from the attack. In the small lake town Minnesota setting Evan is forced into close proximity with a group of teens who have all know each other for years, facing their last summer before college and testing their limits with Last Chance Summer stunts. He is an outsider, welcomed into their circle, but examining their interactions, and his interactions with them, from an emotional distance. He’s trying to figure out what he thinks about girls and sex and life, while dealing with the after-effects of the attack. One girl in particular draws his attention. Baker is smart and complicated and real, and he wants to know her. He wants more than sex. But his attraction for her is terrifying. He now knows sex, even attraction, has consequences. Consequences that can kill you.

It sets the scene for a story about recovery, redemption, and discovering who you are and being willing to discover who other people are – who they really are. Evan’s relationships with his usually absentee but well-meaning father, his therapist, and Baker are all worth the read.

But what is most interesting from a social justice standpoint is what this book has to say about the connections between entitlement and objectification and sex and violence. The Evan from before the attack is part of the same entitlement mindset as the guys who beat him up. The same objectification that allowed Evan to pursue the casual sexual relationships, allows others in the story to resort to violence when they believe the objects of their desires have been coveted, or more, by Evan.

Intertwined with a compelling story is an examination of entitlement, and of how that sense of entitlement can lead to sex and to violence. An examination of the role objectification plays in that triangle. That examination lends itself to conversations and analysis of the messages teens are receiving about sex and violence beyond Evan’s storyline.

If we are concerned with social justice, then it’s nearly impossible not to be concerned with the cultural messages experienced by teens. But when we try to talk about these issues, there’s often an uncomfortable undercurrent of them, those people, not us, are to blame. And too often teens especially struggle with defining rape, with identifying violence, with understanding that too often our culture sends messages about sex and violence that are steeped in objectification and entitlement.

Mesrobian has provided a compelling character through which to examine those connections, and taken him on a journey from entitled self-protection to near destruction to recovery, a journey which requires him to examine his own behavior, and to think about what it means to really be in the moment with another person.