A growing body of literature for middle grade and teen readers explores the lives of child soldiers, young refugees, and other survivors of war. In the past, however, biographies of those who sent others to war often celebrated the feats of the generals, a majority of whom came from the United States or Western Europe. Frequently, military glory was followed by a career in politics – for instance, George Washington, Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, and Dwight D. Eisenhower were elected President, and more recently Colin Powell had a long post-military career in government.

But what about the generals who had second thoughts, who withdrew from the battlefield and spent the rest of their lives pursuing spiritual fulfillment and peace in the communities where they made their homes. This was certainly the case for Abd El-Kader, the Algerian military and political commander whose failed resistance to French occupation led him to the path of peace in the second half of his life.

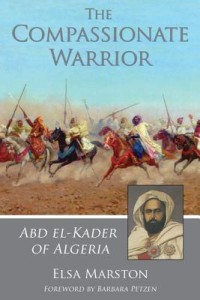

Elsa Marston, the author of more than twenty works of fiction and nonfiction for young readers set in the Middle East and North Africa, offers an exciting and inspiring biography of El-Kader in The Compassionate Warrior. Written for readers middle school age and up, The Compassionate Warrior highlights El-Kader’s childhood, military feats, years of imprisonment, and exile in Syria, where he played a key role in saving lives and promoting peace during the deadly riots in Damascus in 1860.

Elsa Marston, the author of more than twenty works of fiction and nonfiction for young readers set in the Middle East and North Africa, offers an exciting and inspiring biography of El-Kader in The Compassionate Warrior. Written for readers middle school age and up, The Compassionate Warrior highlights El-Kader’s childhood, military feats, years of imprisonment, and exile in Syria, where he played a key role in saving lives and promoting peace during the deadly riots in Damascus in 1860.

Born in 1807, El-Kader was the son of a respected tribal leader in the eastern part of Algeria, and in his early career, he tried to maintain his family’s power in the face of regional hostilities and French occupation of Algeria’s major cities. Marston provides a clear and balanced account of France’s colonial ambitions and indigenous resistance and doesn’t gloss over the atrocities that were part of wartime during that era – for instance, the beheading of suspected traitors and sieges that starved innocent civilians. El-Kader’s resistance to colonial domination earned him worldwide acclaim – Marston points out that the town of Elkader, Iowa received that name because its founder was an admirer of the Algerian leader – but he also gained respect because of his humane treatment of prisoners of war and vanquished populations. In fact, his actions became the foundation many years later of various provisions of the Geneva Conventions.

In the end, however, El-Kader found himself on the run, and he surrendered to the French to protect his people from further suffering. After years of imprisonment, he was allowed to live in exile in Syria. A devout Sufi Muslim, El-Kader called for jihad – holy war – in resisting the French, but in exile, he became a spiritual teacher and risked his own life to save Christians during the Damascus riots. He counted Christians of all backgrounds, including his French captors, among his friends.

Marston’s biography explores the costs of war upon leaders with the empathy to understand its consequences. Few people today outside the Middle East and North Africa have heard of Abd El-Kader, and in Marston’s capable hands, addressing this lack of awareness also means gaining a more nuanced view of Islam and the Muslim world.

2 comments for “A General’s Life After War: Review of The Compassionate Warrior”