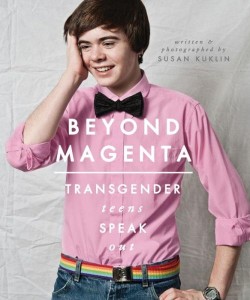

As I wrote last week in the first part of this interview with Susan Kuklin about her new book Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out (Candlewick Press, February 2014), I was thrilled that Susan agreed to be interviewed for The Pirate Tree, so I could ask her some of my reading-inspired questions, and share with others a glimpse into the creative process that produced such an extraordinary book. And since I included an introduction to the book and the interview last week, I’ll dive right into rest of the interview below. I hope you enjoy Susan’s insights and answers as much as I do.

As I wrote last week in the first part of this interview with Susan Kuklin about her new book Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out (Candlewick Press, February 2014), I was thrilled that Susan agreed to be interviewed for The Pirate Tree, so I could ask her some of my reading-inspired questions, and share with others a glimpse into the creative process that produced such an extraordinary book. And since I included an introduction to the book and the interview last week, I’ll dive right into rest of the interview below. I hope you enjoy Susan’s insights and answers as much as I do.

(Strictly speaking, you don’t have to read the first part of the interview before continuing on to the rest of this post, but don’t you want to?)

E.M. Kokie: The visual design of Beyond Magenta is wonderful. The visual presentation of the different teens’ stories varies, some with color photos, one in black and white, one with no photos at all, one of just hands & silhouettes. What factors impacted the visual presentation and design of each section? What challenges did a picture-less chapter pose, or one with photos, but none of the teen’s face?

Susan Kuklin: Each chapter needed to be visually different because each person is distinct. So I knew from the get-go that I wanted a different photographic style for each photo essay. The specific choices came about spontaneously, after getting to know each person. The picture-less chapter and the one where the teen’s face is hidden was not a problem at all. It was important that everyone who took part in the project be completely comfortable. They were given options about the degree of anonymity they could choose. I respected their choices.

When I turned in my first draft, I included electronic images AND high quality color prints. I worked with a teacher from ICP [International Center for Photography] to be sure that each print sparkled. The publisher and I had not talked about using color in a YA nonfiction book. Is color photography used in YA nonfiction? My other YA books are all black and white. The art department reviewed the material and decided to go with the more expensive color. I’m so grateful they did.

Thanks, E.M., for your comment about the visual design. I wanted the book to be modern, simple, and with lots of white, open space. The designer heard me and spent a great deal of time turning my cryptic comments into a concrete layout. She also took great care choosing the right background colors for each chapter. It’s interesting that the colors she ended up with happen to be my favorites. A few of the kids later told me that their chapter’s background color was their all-time favorite color. Nice!

On February 19, I blogged about photographing the teens on INK.

E.M.K.: What about the double-page spread 92-93 — where did that come from? (I spent a long time looking at that spread).

S.K.: You did? I’m so glad. One night when I couldn’t fall asleep I started playing a word game with myself. Some people count sheep, some count presidents. I often think about words. That night I tried to find words that begin with “trans.” It became an eureka moment: wouldn’t it be a interesting to add a list of trans words as a way to “transition” the book its next section? I went up to my studio, turned on the computer, and wrote down words that started with “trans.” That list, somewhat organized and designed, was included with my first draft. The editor liked it. The art department did three designs. My editor and I chose the one that’s in the book. I love it. What does it actually mean? It’s yours to interpret as you will.

E.M.K.: I was really impressed with how honest and open the teens are about their experiences, their lives, their transitions, etc., How did you balance their comfort and safety with telling their true stories honestly? What challenges were there in working your interviews with them into a narrative that was engaging, but showed their voices?

S.K.: The teens chose to be in the book because they wanted their voices heard and because they wanted to help other people. At times they’d ask me to turn off the tape so that they could explain something that was too personal to go into the book. They had a very strong sense about themselves. I transcribed every word in the interviews. I needed to do this to immerse myself in their stories and particular speech patterns. I suspect it’s rather like a novelist hearing her characters’ voices. While actually writing I tried to choose statements that told their story but were not voyeuristic. To be sure that everything was accurate, the teens were invited to read their chapters throughout the editing process.Turning tapes into narratives is part of my creative process. I’ve recently referred to it as “collage writing.” Whereas the collage artist uses found objects to fill a canvas, I use real or found words to fill the page. For this book, though, I added more me to the chapters. It was a literary device to move the narrative forward or give additional information. Collage writing!

E.M.K.: I was also really impressed with how direct and clear you have been in the book, and Candlewick has been in promotional materials, about the terminology and language used in the book and that should be used when writing about each teen. How much of a learning curve did you face in learning the language to tell these stories respectfully?

S.K.: Basically I went from 0 to still learning. It was of the utmost importance that the language in the book be was correct and respectful to both the teens and the transgender community. I learned most of it from the kids. Candlewick was very careful too. They ran the promotional materials by me to be certain everything they sent out represented the community correctly. If I had a question about a word or a phrase, I’d either run it by some of the teens or ask the pros at Callen-Lorde. This became a team effort.

E.M.K.: I was humbled to realize how brave each of the teens is, to live his, her or their lives openly and true to themselves, in a world that hasn’t quite caught up yet. Was it humbling for you, as well, while interviewing and photographing them? Were there also particular moments of inspiration and joy in getting to know them?

S.K.: You bet! That’s why I open the book with a personal statement about how awesome the teens were. Personal moment? It is impossible to choose one moment. Every time I spoke with them was an honor and a privilege.

E.M.K.: How has this experience changed your outlook about gender and sexuality?

S.K.: One of the perks that comes with writing and researching books is that I get to learn something new. I’d like to think that I am more sensitive about sex and gender issues now. I bristle when filling out forms that ask me check “Male” or “Female.” I cringe, and sometimes speak out, when I hear a parent say to their male child, “No, no, you can’t have that. Pink is for girls.” Why??? My life is so much fuller and clearer because of what I’ve learned working on Beyond Magenta.

S.K.: Most of my books are about human rights, civil rights, and freedom of expression. [That also includes books about dance.] It’s basically trying to live the Golden Rule. I think that’s one of the most important lessons for young people. No, an important lesson for ALL people. This has been a thrilling journey.

Susan, Thank you so much for this wonderful, important, beautiful book. And, of course, for the interview!

Susan Kuklin is the award-winning author and photographer of more than thirty books for children and young adults that span social issues and culture. Her photographs have appeared in documentary films, Time Magazine, and the New York Times. Susan lives in New York City.

1 comment for “Beyond Magenta: An Interview with Susan Kuklin (Part II)”