When I was a kid, I devoured books about World War II and the Civil War. These weren’t the only wars that meant anything to me, but they were the only wars written about by children’s authors. In my personal life, my parents were sponsoring Vietnamese refugees, and I was surrounded by men, women, and children who were escaping violence on the other side of the world. Then we moved to El Paso, Texas, where many of the men and women crossing the border “illegally” were refugees from the war in El Salvador. There were zero books for kids about these conflicts.

When I was a kid, I devoured books about World War II and the Civil War. These weren’t the only wars that meant anything to me, but they were the only wars written about by children’s authors. In my personal life, my parents were sponsoring Vietnamese refugees, and I was surrounded by men, women, and children who were escaping violence on the other side of the world. Then we moved to El Paso, Texas, where many of the men and women crossing the border “illegally” were refugees from the war in El Salvador. There were zero books for kids about these conflicts.

These days, “sheltered” American children are exposed to war via their many classmates from around the world who have escaped a conflict zone and are now living in the U.S. Some have parents who have fought in Afghanistan and Iraq; they’ve been deprived of their parents’ presence for long periods of time and now may see the effects of war through PTSD or physical injuries. And of course, many American kids now growing up are either themselves refugees or have parents who were refugees from conflict zones.

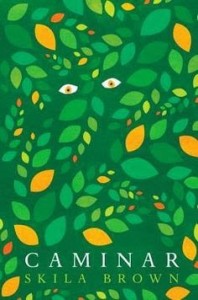

We need more books like Skila Brown’s Caminar to involve children and teenagers in the discussion of violence and war and the far-flung effects of both on societies. Brown’s fierce, lyrical, intense novel-in-verse relates the story of a young boy growing up in Guatemala during war. Carlos wants to defend his village from soldiers. He knows that many young boys fight for the rebels. Alone in the forest when the soldiers decimate his village, he must flee for his life. But knowing that the soldiers are heading for his grandmother’s village at the top of the mountain, he must make a dangerous trek through the forests in an attempt to warn them. Caminar effortlessly weaves together themes of manliness, strength, survival, violence, and grief during Carlos’s journey to the top of a mountain.

Why do you think it’s valuable (or necessary) for kids to read books about war?

Skila Brown: As long as there are people committing heinous acts of violence and genocide, there will be children who survive these tragedies and fold these details into their histories and pasts. I believe that books for kids should reflect the lives kids are living. And just as importantly, we have to remember how powerful books are. How they help us—all of us—to make sense of the world around us. Stories build empathy. Imagine if more of us really understood the consequences of violence? Wouldn’t our society work harder at peace?

I also think survival stories are important. When we see what other people can live through, it makes us stronger. It reassures us that even when life gets hard, we can hang in and find a way to pull through. That’s a message young readers need to hear.

Why do we need to know about the Guatemalan war, in particular? Why should the issues that were being fought over in that war matter to us in 2014?

Skila Brown:The conflict in Guatemala and the history of that country is such a similar story to the history of most of Central America, and other places beyond. Readers in the United States need to understand that our country has historically played a controversial role in this history of violence. When we go in and overthrow democratically-elected governments, when we supply arms, when we bring foreign military personnel to Georgia to train at our School of the Americas (or the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation as it’s now called), we cannot deny a responsibility for their actions, especially when they could later be called genocide.

Every time we intervene in the politics of another nation, we need to be honest about why we’re doing it. The Cold War bred a fear of communism in our country that served as a mask to hide political self-interests. In 1954, it made us so afraid of the word communist that a leader had only to use it, and thus his military actions against a nation were immediately justifiable. Is terrorist our 2014 version of communist? Shouldn’t we be very careful with the words we use and the military action we take?

Your character Carlos loses his home but the concluding chapter shows him returning to his town to commemorate those people he lost. Can you talk about grief and the problems that people encounter grieving the loss of their loved ones when their loved ones were “disappeared” and their stories never concluded or ended?

Skila Brown:I think this can be a kind of torture, really. To never have closure or have any kind of feeling that you know with a certainty your loved one is gone. We’ve heard about it in the news a lot, as I’m typing this, with the search for Flight 370. We hear people saying, “I just want to know what happened.” There are so many people today in Guatemala who want to know the same thing. So many memorial plaques with so many photos of missing people. Families stay in a terrible kind of limbo, unable to really process the grief of their loss, because they don’t know for certain where their loved one is.

Why did you choose to write this as a novel in verse?

Skila Brown:I never made a conscious choice, really, to do that. The story came to me in poems. I assumed I’d use that only as inspiration, but they kept coming and I started to wonder if they weren’t a good fit for this particular story. I think the beauty of a poem is we can spend as much time as we want with it. We can read it slowly, think about each line, let our minds linger on what’s being said and unsaid. Or we can read it quickly, taking in only a portion of what’s there, maybe only what we can handle. By telling Carlos’s story in verse, I think I was able to keep the novel—and the violent details—sparse, leaving this story accessible to readers as young as ten. But the beauty of metaphors and white space is that the story is meaningful for older readers as well. Teens and adults can read the story and understand what’s happening on a different level. The white space, for them, becomes a bridge to connect Carlos’s story with the grief and loss we all have in our repertoire. Verse, I think, gives this story a wider audience.

Skila Brown holds an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She grew up in Kentucky and Tennessee, lived for a bit in Guatemala, and now resides with her family in Indiana. Caminar is her first novel. Click here for an educator’s guide to Caminar.

2 comments for “Walking through Guatemala’s War with Caminar author Skila Brown”