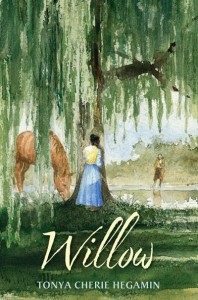

In Willow (Candlewick, 2014), Tonya Cherie Hegamin’s historical novel set in 1848, Knotwild Plantation borders the Mason-Dixon Line between slave state Maryland and free state Pennsylvania. There are no fences or guards—only a stone marker that separates the enslaved black plantation workers from freedom. In her fifteen years of life on the plantation—the only home she has known—Willow has never seen anyone escape. Nor has she considered it for herself.

Although of frail constitution, Willow believes she has a good life as the favored house servant of plantation owner Rev Jeff. Willow has learned to read and write despite it being illegal for enslaved blacks to do so, and she openly corresponds with her master. She lives with her single father, Ryder, who manages the plantation during the frequent absences of Rev Jeff. She doesn’t remember her mother, who was born in Africa, but has pieced together the story from accounts of her father, Rev Jeff, and the ill-tempered black overseer, Cholly Dee. Rev Jeff, who is Ryder’s half-brother (plantation owners like their father frequently raped enslaved black women), basks in the acclaim he receives in the North and Europe for his kind treatment of his slaves, but nearby plantation owners criticize him for being too lenient. Above all, Rev Jeff wants a new wife and Mistress Evelyn from Baltimore threatens to usher in a new regime, one in which Willow will have to be a traditional wife, enslaved both to her master and to the new husband her father has picked out for her.

Although of frail constitution, Willow believes she has a good life as the favored house servant of plantation owner Rev Jeff. Willow has learned to read and write despite it being illegal for enslaved blacks to do so, and she openly corresponds with her master. She lives with her single father, Ryder, who manages the plantation during the frequent absences of Rev Jeff. She doesn’t remember her mother, who was born in Africa, but has pieced together the story from accounts of her father, Rev Jeff, and the ill-tempered black overseer, Cholly Dee. Rev Jeff, who is Ryder’s half-brother (plantation owners like their father frequently raped enslaved black women), basks in the acclaim he receives in the North and Europe for his kind treatment of his slaves, but nearby plantation owners criticize him for being too lenient. Above all, Rev Jeff wants a new wife and Mistress Evelyn from Baltimore threatens to usher in a new regime, one in which Willow will have to be a traditional wife, enslaved both to her master and to the new husband her father has picked out for her.

In the meantime, Cato, a young black man from Pennsylvania has joined the Underground Railroad, and when an accident waylays him near Knotwild, he and Willow cross paths. She begins to questions everything about her life, and whether it’s better to be part of a family and community or to be free and in charge of her own life.

Publishers have come under criticism recently for only focusing on slavery and the civil rights movement when it comes to publishing historical fiction featuring African-American characters. Although Hegamin’s novel fits that pattern, it explores why many enslaved blacks did not flee, even when they had the chance to do so. The social science concept of “false consciousness” addresses why people who are subjugated, mistreated, and vulnerable to even worse treatment do not challenge the status quo. Among the reasons explored in this novel are the family ties that keep Willow tied to the plantation, the fear that things could be worse if she leaves, and the belief that those with wealth and power deserve their privileges and that slavery is divinely ordered. Yet as Willow’s world starts to crumble, she also realizes the double oppression she faces as a black person and as a woman (a concept known as “intersectionality”). Rev Jeff has given her father the right to arrange her marriage to a young man at a neighboring plantation, her future husband will tell her what to do and how to behave, and any children they have will become the property of his cruel master.

Willow is not a perfect book—there are long sections of information dumping, particularly in the parts focusing on Cato’s story, and Cato’s story is in many ways tangential—but it is an intelligent one, with convincing and revealing characters and situations. Hegamin shows that oppression is both physical and psychological. People who experience oppression not only come to accept their unfair status but also perpetuate the injustice by oppressing others who they consider weaker and more vulnerable.

5 comments for “Exploring False Consciousness and Intersectionality: A Review of Willow”