The Friday after Thanksgiving in the United States is traditionally known as Black Friday because of shoppers taking advantage of the long weekend to get a start on their holiday purchases. In recent years, it is also Buy Nothing Day. A project of Adbusters, a Canada-based organization opposed to excessive materialism and predatory capitalism (and best known for its role in sparking the Occupy movement), Buy Nothing Day asks people not to shop on Black Friday and to consider alternative sources for holiday gifts — giving handmade items or the gift of time, buying locally to keep dollars within the community, or choosing products that are made and sold in an ethical manner. This year’s Buy Nothing Day has an added dimension because some civil rights leaders are calling on shoppers to stay home today to show that it’s not “business as usual” following the failure of a St. Louis County grand jury to indict Darren Wilson, the police officer responsible for the shooting death of unarmed teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, this past August.

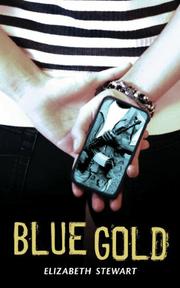

While observing Buy Nothing Day, I’m making my way through the nominees for the Cybils award for Young Adult Fiction (I’m up to 74 of 180 nominees as of today!), and one of the books that sheds light on this dilemma is Canadian author Elizabeth Stewart’s Blue Gold (Annick Press, 2014). Stewart explores the pain caused by a smartphone — one used by a privileged Vancouver teenager to take a semi-nude selfie after a drunken party. Fiona’s picture goes viral, and she becomes a pariah at her school. On the other side of the world, Sylvie lives in a bleak refugee camp in Tanzania with the remnants of her family after fleeing violence in her homeland of Congo, where warlords vying for control of coltan mines have enslaved and massacred the population. Coltan — an amalgam of colombite and tantalite — is essential for the tiny circuits of the smartphone. Coltan, and the other smartphone components, are shipped to and assembled in giant factories in China, where Laiping toils for minimal wages under punishing conditions. In those factories, nets between stairwells keep the abused and desperate young workers from committing suicide on their way between the factories and the dormitories.

While observing Buy Nothing Day, I’m making my way through the nominees for the Cybils award for Young Adult Fiction (I’m up to 74 of 180 nominees as of today!), and one of the books that sheds light on this dilemma is Canadian author Elizabeth Stewart’s Blue Gold (Annick Press, 2014). Stewart explores the pain caused by a smartphone — one used by a privileged Vancouver teenager to take a semi-nude selfie after a drunken party. Fiona’s picture goes viral, and she becomes a pariah at her school. On the other side of the world, Sylvie lives in a bleak refugee camp in Tanzania with the remnants of her family after fleeing violence in her homeland of Congo, where warlords vying for control of coltan mines have enslaved and massacred the population. Coltan — an amalgam of colombite and tantalite — is essential for the tiny circuits of the smartphone. Coltan, and the other smartphone components, are shipped to and assembled in giant factories in China, where Laiping toils for minimal wages under punishing conditions. In those factories, nets between stairwells keep the abused and desperate young workers from committing suicide on their way between the factories and the dormitories.

A labor dispute in Laiping’s factory — which at one point leaves her beaten and stripped of her wages — becomes the subject of another viral video, one that makes its way to Fiona’s community. Fiona also hears of a campaign to rescue Sylvie from a warlord who has claimed her in marriage and to give her a scholarship to a school in Canada where she can pursue her dream of becoming a doctor. But time is running out for both Sylvie and Laiping and their families, and while Fiona wants to help, she has lost the trust of her family.

Stewart’s novel shows how a teenager harmed by a bad decision can move forward by helping others in even more desperate situations. It also shows how our addiction to material things affects people around the world and what it means to make ethical choices when we spend money. If people didn’t demand the latest and greatest smartphone when their current smartphone is working just fine, there would be less demand for conflict minerals, and perhaps governments would have a chance to control violent warlords. And if people bought less and were willing to pay a little more, they could choose products produced and sold locally, ones created under better conditions for the people who actually do the work.