The past ten years have seen 50-year milestones for significant events in the Civil Rights Movement, and with them have come a number of books, fiction and non-fiction, for young readers. Stories of school desegregation, in which a white student becomes enlightened through her or his friendship with a black classmate, are at this point a trope. Often these books are criticized for emphasizing change on the part of the white character, while the ever-patient black character never changes. In her groundbreaking critical work from the 1980s, Shadow and Substance: Afro-American Experience in Contemporary Children’s Fiction, Rudine Sims called these “social conscience” books, contrasting them with the more authentic “culturally conscious” stories by and from the perspectives of African Americans.

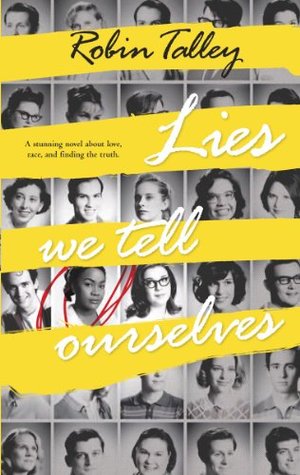

On the surface, Robin Talley’s Lies We Tell Ourselves (Harlequin Teen, 2014) falls into this trope. Talley tells her story of school desegregation in a small Virginia town from the alternating perspectives of Sarah, a black senior and the daughter of civil rights activists who worries about the safety of her younger sister before her own, and Linda, the white daughter of a racist newspaper editor whose engagement to the school’s assistant football coach is her way of escaping her tyrannical father. When Sarah and Linda are assigned to work on a project together, Sarah takes on that role of enlightening Linda about Jim Crow, injustice, and the violence that she and her black friends face every day. For the first time in her life, Linda feels threatened, and her mind begins to change.

On the surface, Robin Talley’s Lies We Tell Ourselves (Harlequin Teen, 2014) falls into this trope. Talley tells her story of school desegregation in a small Virginia town from the alternating perspectives of Sarah, a black senior and the daughter of civil rights activists who worries about the safety of her younger sister before her own, and Linda, the white daughter of a racist newspaper editor whose engagement to the school’s assistant football coach is her way of escaping her tyrannical father. When Sarah and Linda are assigned to work on a project together, Sarah takes on that role of enlightening Linda about Jim Crow, injustice, and the violence that she and her black friends face every day. For the first time in her life, Linda feels threatened, and her mind begins to change.

But there is a crucial twist to this story. Talley is a white LGBTQ activist, and what ultimately draws Sarah and Linda together is their romantic attraction to each other. Linda has promised to marry an older man who she does not love. Sarah finds excuses to avoid dating one of the activist boys. In 1959 lesbian relationships are as taboo as racial integration, and both girls have to overcome their religious upbringing and prying eyes in the course of figuring out who they are and who they really love.

Very few books for teens explore LGBTQ characters and relationships in historical contexts, and even fewer historical novels portray LGBTQ characters of color. For this reason, Lies We Tell Ourselves is a groundbreaking and valuable story, and one that could open the door to more books that portray the intersection of diversities—such as characters of color with disabilities, LGBTQ characters with disabilities, and more. These are not books meant to “pile on issues” but rather ones that reflect the experiences of real people who navigate multiple identities and multiple experiences of ignorance, oppression, and the quest to find a place in the world.