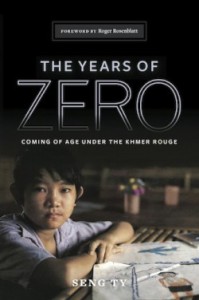

In 1975, when Seng Ty was six years old, Khmer Rouge soldiers forced Cambodians living in the capital city, Phnon Penh, to abandon their homes and begin a march to the countryside, and, for many, to their deaths. Ty has written a memoir, The Years of Zero: Coming of Age under the Khmer Rouge. I interviewed Ty who is now a middle school guidance counselor in Lowell, Massachusetts, the city with the second largest population of Cambodian Americans, after Long Beach. In Lowell, he works with many children who are the third generation of families who survived what has come to be called the Cambodian genocide. This year many events will mark the 40th anniversary of the coming to power of Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot.During his regime 1.7 million Cambodians died.

In 1975, when Seng Ty was six years old, Khmer Rouge soldiers forced Cambodians living in the capital city, Phnon Penh, to abandon their homes and begin a march to the countryside, and, for many, to their deaths. Ty has written a memoir, The Years of Zero: Coming of Age under the Khmer Rouge. I interviewed Ty who is now a middle school guidance counselor in Lowell, Massachusetts, the city with the second largest population of Cambodian Americans, after Long Beach. In Lowell, he works with many children who are the third generation of families who survived what has come to be called the Cambodian genocide. This year many events will mark the 40th anniversary of the coming to power of Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot.During his regime 1.7 million Cambodians died.

Seng Ty, 10 years old, with Roger Rosenblatt who wrote the “Children of War” feature for TIME Magazine. Photo by Matthew Naythons

As Seng Ty recreates his childhood, we meet a boy who is direct, heart broken, and absolutely focused on his responsibility to survive. His story grips the heart with what a child can do to live. He writes that people died mostly of starvation. The diet allowed was rice soup sometimes with three grains of rice. “Most people died of starvation, but some died from illnesses because they no longer had any immunity left.” In one scene he describes his brother Da’s death:

He had become unrecognizable, a skeleton. I laid blankets on the floor to cushion him. It was unbearable to hear the effort of his breathing. “Keep strong, brother,” I said. “Please don’t leave me.” But he could not speak.

Ty tells the deaths of most of his family and one boy he dared to make his friend in the children’s labor camp where they worked. Despite his tragic losses, the story is one of unending courage. He describes his stealth in catching baby mice, roots, crabs. If soldiers caught children finding food, they were killed. He writes, “I had survived…because I was quick, silent, and able to steal.”

Ty brings his story to many middle school, high school, and college classes. I asked him about how he brought such difficult stories to children and teens. He didn’t answer that directly; he expresses his own urgency that young people need to know. He said that when he speaks, even to Cambodian children, “none of the children knew about the Cambodian genocide. Not many in the older generation are talking about it. Even newcomers from Cambodia, even those kids know only a little.” He thinks children, and not only Cambodian children, should understand this history and that sharing the story of those who died honors them and keeps them alive.

Ty says students often tell him about struggles with their families and in their cities in the U.S. He explains that his story also offers hope to students who have many problems today. He tells them, “Even if you have a difficult home situation, you can go for help. Come to school [in the U.S.], you can have a meal.” He said he wants students to see how important education is. His mother had died from starvation but he repeats her words to students today, “No one can steal your knowledge.”

Seng Ty was one of the children interviewed in Children of War by Time Magazine reporter, Roger Rosenblatt. He was 10. Rosenblatt met him soon after Ty escaped to Khao-I-Dang refugee camp in Thailand. Ty told me the same thing he told Rosenblatt when he was a child. He said he wished there would be truth-telling in Cambodia today and that people should confess what they did during the war, but he is not angry. He said, “To me, revenge means that I must make the most of my life.”

His story gives young readers extraordinary ideas to wrestle with about themselves and about the world.

6 comments for “Seng Ty’s Years of Zero: Coming of Age under the Khmer Rouge”