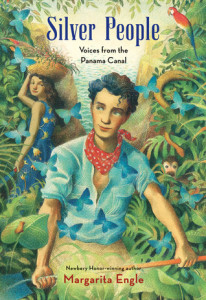

While many younger readers in the United States have learned of the civil rights struggle in the South, the story of the Panama Canal has been taught as a heroic conquest of humans against nature. In a powerful novel in verse narrated from multiple perspectives—including the trees and forest creatures—Margarita Engle’s Silver People: Voices from the Panama Canal challenges both parts of this story. Readers see the racial segregation—the white American engineers paid in gold, and the olive-skinned Spanish and black Jamaicans and other islanders paid in silver—as well as the destruction of the environment and its fatal consequences.

Engle’s principal storyteller is Mateo, a Cuban boy who signs a contract to build the canal at age 14 to escape his father’s abuse. Nearly ten years after the end of the Spanish-American War, Mateo’s father, a former revolutionary, is a broken alcoholic, and many Spaniards who fought on the losing side are stranded and looking for work. Mateo pretends to be one of them, for the labor contractors are only hiring men with pure European blood. In Panama, Mateo discovers only broken promises—low wages, substandard living conditions, bosses who care nothing for their workers, and bunkmates, Spanish anarchists, who denounce the clueless adolescent to protect themselves. Used to fighting, Mateo spars with a Jamaican worker, Henry, who has signed a labor contract to provide money for his younger siblings’ schooling but discovered that his low wages (the black workers make only half of what the Spaniards make for the same jobs) aren’t even enough to pay his expenses. Anita, an indigenous girl who trades him herbs for paintings, and Augusto, a Puerto Rican engineer and master painter who finds himself demoted from “gold” to “silver” after the bigoted George Goethals takes over the project, help the young Mateo as he struggles to survive. While escape into the forest may be Mateo’s only option—an option made more difficult by his bouts with malaria—the consequences of getting caught trying to escape a contract are horrific.

Engle’s principal storyteller is Mateo, a Cuban boy who signs a contract to build the canal at age 14 to escape his father’s abuse. Nearly ten years after the end of the Spanish-American War, Mateo’s father, a former revolutionary, is a broken alcoholic, and many Spaniards who fought on the losing side are stranded and looking for work. Mateo pretends to be one of them, for the labor contractors are only hiring men with pure European blood. In Panama, Mateo discovers only broken promises—low wages, substandard living conditions, bosses who care nothing for their workers, and bunkmates, Spanish anarchists, who denounce the clueless adolescent to protect themselves. Used to fighting, Mateo spars with a Jamaican worker, Henry, who has signed a labor contract to provide money for his younger siblings’ schooling but discovered that his low wages (the black workers make only half of what the Spaniards make for the same jobs) aren’t even enough to pay his expenses. Anita, an indigenous girl who trades him herbs for paintings, and Augusto, a Puerto Rican engineer and master painter who finds himself demoted from “gold” to “silver” after the bigoted George Goethals takes over the project, help the young Mateo as he struggles to survive. While escape into the forest may be Mateo’s only option—an option made more difficult by his bouts with malaria—the consequences of getting caught trying to escape a contract are horrific.

Engle’s free verse is vivid and eloquent. So much is said with very few words. Equally poignant are the poems from the perspectives of howler monkeys, who scream for the invaders to “GO!”; the mosquitoes, snakes, and vultures who threaten the men; and the trees that fall to the men and machines, wishing they could “run / leap/ fly” to escape as well. This novel has wide appeal, from reluctant readers to serious history buffs, and it provides an essential counterpoint to the textbook narrative of the canal’s construction. At a time when Nicaragua has become the target of another canal-building project (this time initiated by a Chinese enterprise), the book offers a vision of what will happen and a lesson on the importance of knowing our history.