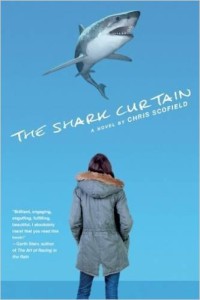

I was enormously privileged to be the editor for Chris Scofield’s The Shark Curtain, which came out on the Akashic YA imprint Black Sheep earlier this year. The moment I read this book, I understood that Scofield was doing something dramatically different in YA fiction and I was eager to see what she was going to do with the book. To introduce the book, I’m going to rely on the publisher’s description and then segue into an interview with Scofield about the enormously challenging issues she seeks to explore.

“Set against the changing terrain of middle-class values and the siren calls of art and puberty, The Shark Curtain invites us into Lily Asher’s wonderful, terrible world. The older of two girls growing up in suburban Portland, Oregon, in the mid-1960s, her inner life stands in quirky contrast to the loving but dysfunctional world around her. Often misunderstood by her flawed but well-intentioned parents, teenage Lily orbits their tumultuous love affair, embracing what embraces her back: the ghost of her drowned dog, a lost aunt, numbers, shoe boxes, werewolves, rituals, and stories she pens herself (including one about a miscarried sibling she dubs “Frog Boy”). With “regular” visits from a wisecracking Jesus, an affectionate but combative friendship is born—a friendship that strains Lily’s grasp of reality as much as her patience.From the violence of a Peeping Tom and catching Mom in flagrante delicto with the neighbor, to jungles in her closet, butlers under her bed, and barking in public, Lily struggles to balance her family’s expectations with the visions that continue to isolate her.”

One of the most touching aspects of SHARK CURTAIN, to me, is the loving but enormously fragile relationship Lily has with her mother, Kit…

Scofield: Thanks, I’m pleased you see it as “loving but fragile.” To a lesser degree, I think all Lily’s relationships are that way. There are no “bad guys” in The Shark Curtain. Maybe Mr. Marks is a bad guy…

In my personal and professional experiences, even traveling as much as I have, I believe most parents do the best they can with what abilities and resources they have. I think most people love their children. I suspect I’m sounding terribly naïve here. I’m not blind to tricks of child molesters for instance.

The mother-daughter dynamic is fraught with such emotional weight in both real life and in your book.

Scofield: Indeed it is! I think when a mother is probably clinically depressed, has addiction problems, and is a “frustrated artist” (by that, I mean, Kit did not have enough opportunity to explore and invest herself in her talent), there are a number of issues at work. And Lily of course is a huge challenge. Kit wants to do the right thing by her, wants to be a “good mother,” to help her and understand her. But being orphaned herself at Lily’s age, the modeling of a maturing relationship wasn’t there for Kit. Kit’s as close to Lily as she’ll ever be—which speaks to Kit’s neediness. (Including the slap and the rupture in her marriage; Kit and Paul have to be tighter now, more united in order to save their marriage.) Despite Lily’s age/hormones, she has an awareness that she’ll always be dramatically, poignantly different; but to survive, to have any healthy autonomy, she must acquire some conventions of living in “real life” (this thing the rest of us call real life, anyway). I’ve worked with autistic kids who knew they were different from their peers, who knew they didn’t fit in, and there is nothing romantic or provocative about it. All of us (teenage rebels or teenage Lilys) want to fit in somewhere.

Many YA authors choose to ignore this issue altogether.

Scofield: Yeah, it’s not very sexy.

Can you talk about the difficulties and joys of making this mother-daughter relationship the centerpiece of your story? Why is the mother-daughter dynamic so important? Why did you focus on it?

Scofield: I see Lily and Lauren as “second tier” family members orbiting around their parents’ tumultuous relationship (Paul and Kit have it bad for each other) yet “the shark curtain” itself orbits around Lily and Kit’s relationship. For me, personally, it’s all about Lily though. It’s sometimes challenging to write about a main character who isn’t main to the other main character, you know what I mean? I think Kit would see the book, The Shark Curtain, as all about her—her dysfunction, her love, her art, her neediness, the way Lily (as much as Kit loves her) sometimes embarrasses her…..I think it would be difficult to live in that household where Kit pretty much ruled the roost without being dramatically affected by her manic swings. Also, I think she’s jealous of Lily’s detachment. She voices a resentment or enviousness once or twice. Kit is a contradiction of terms—she wants the security and fantasy of respect that comes with upward mobility yet I wonder if she wouldn’t throw it all away and run off to a Greek island if she had the chance? Her family (Lily included) might wonder that too.

Frankly, I’m surprised that I write so much about family (or different notions of family.) I was earnestly rebellious when I was Lily’s age and I couldn’t wait to get away from mine! Maybe that’s why!

Lily’s parents love her but they grow weary and frustrated dealing with her personality problems.

Scofield: It would be exhausting. The minute they had something figured out, Lily would come up with something new.

However, I found it interesting that you always choose to have one parent emotionally ready to love and accept Lily even as the other parent is ready to give up on her.

Scofield: I think with some kids, and with Lily in this case, it takes amazing energy, focus, patience, mindfulness AND imagination to always be available for her behaviors (good and bad). They don’t know how far she’ll go with her fantasies or her denial, the risks she takes out of ignorance or as an expression of her imagination. She’s unpredictable, possibly even dangerous. She’s haunted by visions and ideas and fantasies her family’s not privy to. Her inner life is rich in ways they’ll never be able to understand. Thank God she has her art. Lily’s art (shoeboxes) is pretty much right from the tap but, like Kit’s, it’s also a valve, releasing tension and fear, giving herself permission to play.

To have a child like Lily who is so profoundly different, so profoundly distant, would be scary. Then, to complicate things further, here come the hormones!

Though both parents may momentarily band together against her, one always pulls back in time before Lily is thoroughly, completely rejected.

Scofield: They love her, they really do. But they’re only human and figuring things out for the first time; she’s their first child, after all. I think parents, not always hip to the impression they’re making on their kids, trade off discipline-wise sometimes (like spelling a boxer), good cop-bad cop. I don’t know if Paul and Kit do that consciously but….

Can you discuss this child-parent/parenting dynamic as it played out in your book? Have you had experience with this kind of ambiguous, even ambivalent, parental response to a difficult child?

Scofield:This may or may not answer your questions: working with emotionally disturbed kids in self-contained classrooms, a person is witness to all kinds of kid-parent dynamics. I have a picture permanently stamped in my brain of one of the meanest kids in our classroom greeting his stoned meth-head biker parents at the door to school one afternoon. They’d come for an IEP meeting. I’d never seen mom and dad together before, as one or both of them always seemed to be getting out of or going into jail. The boy/our student held their hands as he walked between them down the hall to our classroom, his little face ping-ponging between them, prompting Dad to “Tell Mom how nice she looks.” Nearly broke my heart. Poor little guy….There are adults too self and self-absorbed to parent a child fairly; people who never grew up themselves. The biker stoner parents are like that, Kit and Paul aren’t….

I think we’re all a little damaged by our parents. I think we’re all a little damaged by our kids. It’s always personal between us—parents and kids, kids and parents—and loaded with potential to disappoint each other, say too much, make the wrong choice, hurt each other. If we weren’t so important to each other, it wouldn’t matter. But love is important and it’s messy. Kit and Paul are messy. Lily understands that. She forgives and forgets, and moves on. She knows she’ll always be some kind of weirdo.

I’m a little surprised when someone tells me they’re scared for Lily and hope she’ll be OK. I think she’s OK. The fact that Jesus is still visible to her when she wants to be done with him suggests there still work to be done though. Schizophrenia or imagination overdrive, whatever it is, doesn’t just happily conveniently skip away. Lily’s messy too and like the rest of us, she’ll continue to be.