During the devastation of Hurricane Sandy, the Dutch author Anna Woltz and I switched places. She was hunkered down in New York City while I followed the news from the safety (and sunny weather) of Lisbon, Portugal. But she turned her frightening experience into a page-turning novel, translated by Laura Watkinson and published by the Arthur A. Levine imprint of Scholastic.

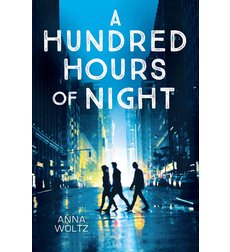

A Hundred Hours of Night begins with 15-year-old Emilia December de Wit boarding a trans-Atlantic flight with pages of forged documents, running away from a scandal involving her school-principal father. The revelations have led to lewd and threatening social media posts directed to Emilia and her mother, an Irish-born artist who makes excuses for her husband because he lets her neglect her family for her art. The scandal has destroyed Emilia’s world, ruptured her already-few friendships, and exacerbated her OCD into a full-fledged crisis on the airplane. Nonetheless, Emilia crosses into the U.S., only to discover that the apartment she booked on Craigslist is a scam.

A Hundred Hours of Night begins with 15-year-old Emilia December de Wit boarding a trans-Atlantic flight with pages of forged documents, running away from a scandal involving her school-principal father. The revelations have led to lewd and threatening social media posts directed to Emilia and her mother, an Irish-born artist who makes excuses for her husband because he lets her neglect her family for her art. The scandal has destroyed Emilia’s world, ruptured her already-few friendships, and exacerbated her OCD into a full-fledged crisis on the airplane. Nonetheless, Emilia crosses into the U.S., only to discover that the apartment she booked on Craigslist is a scam.

The scam leads her to the doorstep of 16-year-old Seth, who is watching his precocious but also distressed 11-year-old sister while their mother is out of town. Their 17-year-old neighbor, Jim – like Emilia, a runaway – faces a crisis of his own when an accident at an illegal job nearly severs his finger. The four youngsters are thrown together when Hurricane Sandy hits and plunges them into a fearful darkness for days. Emilia is forced to cope with circumstances she’d never imagined, and help three other people with their own crises.

Woltz’s exciting coming-of-age story offers an outsider’s perspective on American culture – the good, the bad, and the ugly. The son of an unemployed factory worker in Detroit, with his mother forced to work two jobs to make ends meet, Jim detests the capitalist system. He has dropped out of school and run away because he sees no future for himself. Emilia comes from a country where health care is available to all and people aren’t thrown into the streets, but the viciousness of the social media attack against her family (including her and her mother, innocent victims) show the underside of a small, insular society.

That said, we in the United States aren’t immune to vicious social media attacks, and to some extent, Woltz and her protagonist idealize the U.S. in much the same way Americans may idealize life in Europe. The great thing about reading this novel in translation is that we see how others view us and themselves. Emilia’s struggles with OCD and with her family are ones that cut across cultures, but we should also pay attention to the different perspectives and experiences of outsiders who help us to think about our daily lives in new ways.