At the 1960 Olympic Games, African American sprinter Wilma Rudolph became the first woman from the United States to win three gold medals at the same Olympics. Rudolph grew up in Clarksville, Tennessee, a segregated town. After her victories, Rudolph became a household name, and Clarksville wanted to honor her with a parade and banquet. Rudolph agreed on one condition — that the celebrations be integrated. The celebrations for Rudolph were the first major integrated events in Clarksville.

At the 1960 Olympic Games, African American sprinter Wilma Rudolph became the first woman from the United States to win three gold medals at the same Olympics. Rudolph grew up in Clarksville, Tennessee, a segregated town. After her victories, Rudolph became a household name, and Clarksville wanted to honor her with a parade and banquet. Rudolph agreed on one condition — that the celebrations be integrated. The celebrations for Rudolph were the first major integrated events in Clarksville.

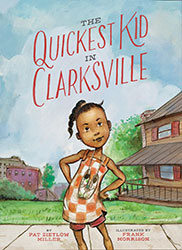

The Quickest Kid In Clarksville, text by Pat Zietlow Miller, illustrations by Frank Morrison (Chronicle Books, 2016), imagines the impact of Rudolph’s victories and the resulting celebrations through the eyes of young Alta, who idolizes Rudolph, and who considers herself the fastest kid in town. That is until new girl Charmaine shows up with her flashy new running shoes (just like Rudolph’s!) and swagger to match. The girls have a series of races, splitting the outcomes, and parting far from friends. Alta limps home with a sore toe and a hole in her shoe — a shoe that has to last for a while because, unlike Charmaine, Alta’s family can’t afford new ones.

When the day of the parade dawns, Alta struggles to carry her homemade banner to the parade route. Charmaine comes to her rescue, reminding Alta that one of Rudolph’s medals was for a relay race, which she didn’t win alone. Alta, Charmaine, and two of Alta’s friends take turns carrying the banner. They land perfect spots to watch the parade, and, even better, Rudolph smiles and waves at the new friends from her float.

Miller’s text keeps the story firmly in Alta’s point of view — focused on being the fastest, running to the rhythm of Wil-ma Ru-dolph, comparing Charmaine’s fancy new shoes with her own never-thought-to-glimmer ones, and dragging home “[f]eet dragging…head hanging” when she loses the second race to Charmaine. Even Alta’s excitement about the parade is focused on a child seeing her idol, rather than any of the larger social implications of the parade or Rudolph’s victories.

Morrison’s expressive watercolor illustrations perfectly capture the girls’ respective personalities and emotions, as well as their movements as they run, leap, and bound through the story.

While the story itself stays focused on the girls, a detailed author’s note provides more information about Rudolph and context for the social implications of her historical victories and the resulting celebrations. A black and white photograph of Rudolph in the parade adds to the authenticity of the story, and may help younger readers connect the story with history.

While many young listeners and readers will ask for The Quickest Kid In Clarksville for its plot and language, the story may also allow for age appropriate discussions about friendship, rivalries, envy, sports, and the historical context of the underlying events. Plus, with the 2016 Olympic Games set to open in just a few weeks, it couldn’t be a more timely book to share.