People in the United States who are now seeing their freedoms and rights eroded one by one, from reproductive rights to safety and living-wage protections for workers to the right to protest, and who believe this is a new thing ignore the fact that African-Americans have lived under police-state conditions since arriving in chains to the New World. Abolitionism and the Civil Rights Movement are examples of the success that courageous Black activists have had in moving the United States toward its democratic ideals, but progress has often stalled and at times we have moved backward. Great literature faces these conflicts honestly and offers insight drawn from the experiences of authentic and real characters that touch readers’ hearts. Angie Thomas’s debut YA novel, The Hate U Give, is one of those books, an important story for our time.

People in the United States who are now seeing their freedoms and rights eroded one by one, from reproductive rights to safety and living-wage protections for workers to the right to protest, and who believe this is a new thing ignore the fact that African-Americans have lived under police-state conditions since arriving in chains to the New World. Abolitionism and the Civil Rights Movement are examples of the success that courageous Black activists have had in moving the United States toward its democratic ideals, but progress has often stalled and at times we have moved backward. Great literature faces these conflicts honestly and offers insight drawn from the experiences of authentic and real characters that touch readers’ hearts. Angie Thomas’s debut YA novel, The Hate U Give, is one of those books, an important story for our time.

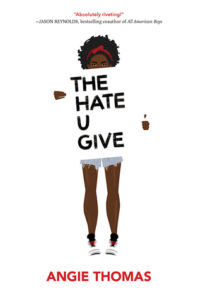

The Hate U Give is inspired by THUG LIFE, Tupac Shakur’s famous acronym that stood for “The Hate U Give Little Infants F***ks Everybody.” (Sorry, but this is a family-friendly blog.) It is both a statement that Black lives matter and the story of a 16-year-old girl, Starr Carter, with her own life and problems who is thrust into the spotlight when she accepts a ride home from a party with childhood friend Khalil, only to watch police stop the car and shoot him before her eyes. Her beloved uncle is a police officer, caught in the middle when she bravely testifies against Officer One-Fifteen, who treated her and her friend abusively before gunning down her friend. Starr, whose mother is a nurse and whose father owns a grocery store in their mostly poor, mostly African-American community, attends a private school in a suburb 45 minutes away and navigates the two very different worlds, serving as a guide to readers through her first person narrative. Hardly an activist before the shooting (though a picture of Emmett Till’s body that she posted on her Tumbler the previous year led to tension with one school friend), Starr learns both the importance of and the costs of speaking out. Often the cognitive dissonance – she writes, “I hope none of them asks about my spring break. They went to Taipei, the Bahamas, Harry Potter World. I stayed in the hood and saw a cop kill my friend.” – seems too much for her to bear.

But this isn’t only one teenager’s story. The spotlight on Starr’s community, and differing approaches to confronting its militarized occupation, ignites a gang war that threatens her father even though he left that part of his life behind years earlier. Strong, complex secondary characters enhance this collective story, as readers grow attached not only to Starr but also to her supportive parents, her two brothers, Khalil’s family, and another troubled teen, DeVante, who lost his brother to gang violence and now wants to escape. Throughout the novel Thomas captures this tension between escape and staying to bring about change. It is an important tension, and one that may grow in significance in the coming years.

This #ownvoices novel takes its place within the growing body of post-colonial literature, demonstrating that books written principally for teen readers belong to this canon. A hallmark of colonialism is the belief that some lives matter more than others, and while we shouldn’t have to prove otherwise (because it should be accepted that we all have the same rights because we are human), those who create the stories, bearing witness through their writing, are the ones who will build a culture and society based on justice and respect for all.

2 comments for “The Literature of Witness and The Hate U Give”