On August 19, 1953 a clandestine military operation led by the United States and Great Britain toppled the democratically elected government of Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran and installed Shah Reza Pahlevi, who immediately reversed Mossadegh’s nationalization of oil facilities. For the next 24 years the Shah would rule with an iron fist, repressing both liberal democrats and conservative Muslims. The 1979 Iranian Revolution united both of these factions in their anti-Americanism, but it soon became clear that the Muslim Ayatollahs held the power and would wield it against all enemies of their theocracy.

On August 19, 1953 a clandestine military operation led by the United States and Great Britain toppled the democratically elected government of Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran and installed Shah Reza Pahlevi, who immediately reversed Mossadegh’s nationalization of oil facilities. For the next 24 years the Shah would rule with an iron fist, repressing both liberal democrats and conservative Muslims. The 1979 Iranian Revolution united both of these factions in their anti-Americanism, but it soon became clear that the Muslim Ayatollahs held the power and would wield it against all enemies of their theocracy.

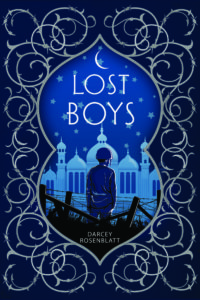

This context is important in understanding Lost Boys, Darcey Rosenblatt’s debut novel for older middle grade readers. The novel begins in 1982, after the Ayatollahs have consolidated their power and are now mired in a war against Iraq, which took advantage of its neighbor’s revolutionary chaos to invade. Twelve-year-old Reza admires his uncle, an intellectual who opposes the government, but his mother thinks the uncle is a fool and a subversive who will get the entire family in trouble. Reza’s mother has become a loyal supporter of Ayatollah Khomeini and the war, and she hopes that Reza will become a martyr like his father. Reza’s best friend, Ebi, raised on war movies, can’t wait to join the army, but Reza doesn’t want to die. He only wants to live in a country where he can play music, the way he did before the revolution.

After his uncle’s death, though, Reza loses all hope for his music. Angry at his mother, he enlists along with Ebi, and the two become child soldiers. Too small to shoot a rifle, the children are tied together and forced to run through minefields so the older soldiers can follow and attack. Separated from Ebi, Reza is wounded and ends up in an Iraqi POW camp, where he must dodge a sadistic guard and a fanatical fellow prisoner who lashes out because he has lost his chance at martyrdom. Through it all, Reza dreams of playing music again, a dream that may become a reality when the Red Crescent sends a teacher to the camp, and searches for his lost friend.

While describing a time and place in concrete detail, down to the sand that gets into eyes, clothing, and food, Rosenblatt explores the universal themes of friendship and loss. While peer pressure plays a role in Reza’s enlistment in what is essentially a children’s suicide mission (and a war crime among many in that eight-year-long war), friendship ultimately sustains him and the other boys who spend much of their adolescence in the perilous limbo of the Iraqi POW camps. Like many of the boys who are caught up in revolution and war, Reza has experienced loss and grief. He has already lost his father to the war, and his mother “said she’d be proud to have me die.” He has lost his music, the greatest source of pleasure in his life and a talent he has that will surely go to waste. Then Reza loses his uncle, just after his uncle holds out hope that he may one day study music in a freer country. Rosenblatt makes the reader feel each of these losses and wonder how Reza can take any more without giving up completely.